In recent years, approximately 72 million Europeans—representing 17% of the European Union’s population—have been classified as living in poverty. However, the current definitions of poverty have only been in use since the early 2000s. What, then, was the situation prior to that? Since when, and by what methods, has poverty been measured? What developments have taken place over the last century since the first conceptual frameworks emerged in Britain?

This blog post, connected to my article in Social History 50.3, seeks to address these questions. It invites readers to adopt a broader perspective on poverty: not merely as a set of material conditions, but as a social and political construct shaped by contemporary ideas and policy choices. The analysis focuses on the period from 1950 to 1970—a timeframe that, while extensively explored in the United States, is now attracting growing attention among European historians. Special attention is given to the French context, examining both the numerous experiments and missteps, as well as the transnational influences and exchanges that informed evolving approaches to poverty.

The 1950s–1970s in France: A hesitating Approach to Poverty

With the pioneering work of Charles Booth in London and Benjamin S. Rowntree in York, the United Kingdom took an early lead in the study of poverty at the end of the nineteenth century. Their research established the notion of so-called absolute thresholds, grounded in the minimum material needs of individuals and households. This approach, later revised, was adopted by the United States in 1965 with the introduction of its official poverty line and statistical framework, and subsequently adapted—albeit differently—by the World Bank in the 1990s. In contrast, neither France nor most European countries ever embraced the concept of absolute thresholds. Instead, they moved toward a relative conception of poverty, formally adopted between 1975 and 1981. What precisely does this relative approach entail, and why was it chosen?

To understand this shift, we must look slightly earlier, to the period from 1950 to 1970. These decades have garnered increasing attention in poverty research—first in the United States, where the “War on Poverty” quickly became a subject of historical inquiry, and more recently in Europe. In France, it was long assumed that poverty was largely absent during the so-called Trente Glorieuses (Glorious Thirties)—a period marked by strong economic growth, the rise of a consumer society, and exceptionally low unemployment. This assumption, however, does not withstand scrutiny.

In mid-twentieth-century France, poverty was indeed conceptualized quite differently from today. Rather than being seen as a unified social issue, it was associated with distinct problems and target populations—each thought to be rooted in specific, unrelated causes. These included the elderly, many of whom had not yet reached retirement age; people with disabilities, who remained largely invisible in public discourse; migrant workers and slum dwellers, whose numbers increased dramatically in urban centres to support industrial expansion; small rural shopkeepers suffering from economic decline.

Inspired by initiatives in Belgium and the United States during the 1950s, the French approach began to involve identifying and quantifying vulnerable social groups. Between 1965 and 1974, a significant body of work emerged, spearheaded by Catholic organizations on one side and state institutions on the other. Estimates of the number of poor varied widely—from 2.7 to 15 million, with most converging around 10 to 12 million, out of a total population of approximately 50 million.

These figures suggest that “poverty in affluent societies” should no longer be considered a marginal phenomenon. The notion of “pockets of poverty,” popularized by American studies, appears to be a striking understatement—these “pockets” resemble vast “continents.”[1] In fact, contemporary reconstructions indicate that poverty rates during this period were substantially higher than they are today, despite the economic prosperity of the time and in contrast to today’s context of mass unemployment.

This ambiguity arises primarily from the diversity of thresholds employed in aggregating these populations: in some cases, assistance thresholds were used, which varied depending on the specific target groups and the nature of the benefits provided; in others, income thresholds were applied to working individuals, though often defined in an arbitrary manner. This methodological inconsistency compels to consider alternative approaches.

Towards a Relative Conception of Poverty in Europe

The magnitude of the figures cited above also helps to explain why an absolute approach to poverty was ultimately not adopted. According to Rowntree’s criteria, poverty was presumed to have nearly vanished in the United Kingdom by the early 1950s—a conclusion that was, in reality, far from accurate. In response, a growing body of thought began to challenge the adequacy of absolute measures. Influential figures such as John Kenneth Galbraith in the United States, and Peter Townsend and Brian Abel-Smith in the United Kingdom, championed a relative conception of poverty [2] — one that considers individuals’ living standards in relation to the broader conditions of the society in which they live:

individuals, families and groups in the population can be said to be in poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the type of diet, participate in the activities and have the living conditions and the amenities which are customary, or at least widely encouraged or approved, in the societies to which they belong. Their resources are so seriously below those commanded by the average family that they are, in effect, excluded from ordinary living patterns, customs, and activities.[3]

In France, this emerging relative approach to poverty found a particularly receptive audience in a small, yet rapidly growing organization: ATD Fourth World. Initially modest in scale, ATD Fourth World would go on to play a significant role in shaping public and institutional discourse on poverty. This post draws partly on my latest book devoted to the ATD Fourth World organization, which also inspired the research questions explored here.[4] Committed to fostering transatlantic dialogue and intellectual exchange between Europe and the United States, ATD Fourth World sought to deepen understanding of poverty in affluent societies and to raise awareness among European institutions.

It was in this context that, in 1975, European authorities formally adopted a relative definition of poverty, describing it as a condition affecting “individuals or families whose resources are so limited as to exclude them from the minimum acceptable way of life in the Member State in which they live.” This marked a significant shift in the conceptualization of poverty, grounding it in the relational standards of each society.

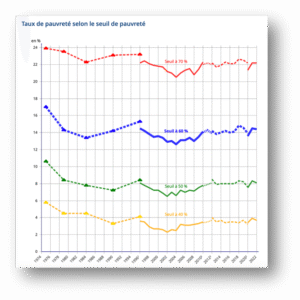

The poverty threshold subsequently evolved in several stages: initially defined as 50% of average income, it was later recalculated as 50% of median income, and, since the 2000s, has been set at 60% of median income. Any household with an income below this threshold is classified as poor. The 10-percentage-point increase is far from trivial: in France, applying the 60% threshold yields 9.2 million people living in poverty, compared to 5.3 million under the 50% threshold. The adoption of a relative threshold also has important implications: it reflects inequality more than absolute deprivation, and implies that poverty, as defined, will always exist—regardless of overall wealth levels.

What the History of Measurement Reveals About the History of Poverty

The question of how poverty is measured reflects, then, broader conceptual frameworks and institutional approaches—across academic research, non-governmental organizations, national governments, European bodies. Measuring poverty also presupposes awareness of the issue; a desire to represent it systematically; the deployment of statistical resources; and the making of methodological choices. It also entails political implications: to generate figures is to construct it as a public problem and to acknowledge the necessity of addressing it. In this sense, the methods of measurement reveal, more broadly, how the poor are perceived, understood, and socially constructed within a given society. That is also why this discussion contends that the period from the 1950s to the 1970s in Europe witnessed both a rediscovery of poverty within affluent societies, and a reconstruction of poverty as a multidimensional social, economic, and political reality.

The shift toward a relative conception had far-reaching political consequences. By highlighting inequalities, it introduced new dimensions to the fight against poverty—emphasizing exclusion from acceptable standards of living, the right to a decent standard of life, and the experience of multiple deprivations. This represented a move away from purely monetary definitions toward a more multifaceted understanding of poverty.

Paradoxically, however, 1975 also marked the turning point between post-war prosperity and economic crisis. The 1980s witnessed a partial return to absolute conceptions of poverty, focusing once again on income deficits, food insecurity, substandard housing, and other basic needs—accompanied by a relative retreat from the ambition to reduce inequality.

Axelle Brodiez-Dolino is a research director at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), France. Her work encompasses histories of poverty, precarity and solidarity initiatives.

References

[1] Économie et humanisme, Introduction to the first part, no 174 (« Pauvres et pauvreté dans les sociétés riches »/ “The poor and poverty in rich societies”) (1967), 15-16.

[2] Peter Townsend, “Poverty: Ten Years after Beveridge”, Planning, n° 344 (1952); Peter Townsend, “The Meaning of Poverty”, British Journal of Sociology, 13,3 (1967), 222-227; Brian Abel-Smith and Peter Townsend, “The Poor and the Poorest”, Occasional Paper on Social Administration, n° 17 (1965).

[3] Peter Townsend, Poverty in the United Kingdom. A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living (Harmondsworth, Middx, Penguin, 1979), 31.

[4] Axelle Brodiez-Dolino, ATD Quart Monde, une histoire transnationale. La lutte contre la pauvreté, d’un bidonville à l’ONU (ATD Fourth World, a transnational History. The fight against poverty, from a shanty town to the UN), (Paris, 2025).