In 2023, a six-week strike by the United Auto Workers led to major wage and benefit gains for workers at America’s “Big Three” car makers – General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. The strike received widespread public attention, with a Gallup poll showing that 75 percent of Americans supported the UAW in its fight for higher pay and more job security.[1] In September, President Biden even walked the UAW’s picket line in Belleville, Michigan, the first sitting U.S. president to join a picket line. “Unions built the middle-class,” he asserted. “That’s a fact.”[2]

Biden’s action reminds us that strikes – a unique expression of citizens’ frustration – matter. In particular, the 2023 walkout showed the ability of big auto strikes to capture broader attention. BBC News, The Guardian, and Reuters were among those there, seeing the dispute as integral to a broader upsurge in labour activism that was linked to the rising cost of living, a tight labor market, and wage stagnation. Overall, 2023 would witness a “hot labor summer” of strikes in the U.S., the number of walkouts reaching levels not seen in decades.[3] In the wake of the pandemic, there were similar trends elsewhere; in 2022, the number of working days lost to strikes in the UK rose to the highest level in over a decade, while the EU Observer reported a “new surge of industrial action” across Europe.[4]

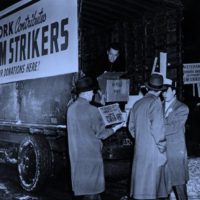

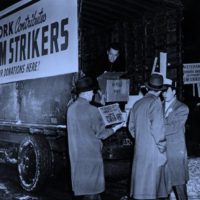

GM workers on strike in the autumn of 1945. Their request for a 30% pay rise had been refused.

In particular, there are parallels with a huge strike at General Motors (GM) in 1945-46. Part of my wider research on the U.S. auto industry, this article was completed as the 2023 strike unfolded. Both were important events that were led by the UAW, an 88-year old organization that was for decades America’s biggest industrial union.[5]

Continue reading →