Even though male homosexuality was decriminalised in Britain in 1967, it still occupied a legal grey area in which it could be classified as an ‘unlawful’ act contrary to the public good. This was because of the revival of a common law offence known as ‘conspiracy to corrupt public morals’ which was applied to those gay men who were advertising in the new gay press for friends and lovers. This fact perturbed more than a few such advertisers. For instance, in the summer 1973, a man named Tony wrote in to the new gay magazine Jeffrey from his home in Leicester. The previous June he had placed two lonely hearts ads in a different magazine, using words that he admitted were ‘pretty strong to say the least,’ though he ‘thought they would be OK.’ He had, he wrote, since heard that ‘it was illegal to use such adverts and that the person advertising could be prosecuted “for conspiring with others to corrupt public morals”.’ After that nasty surprise, he had withdrawn the ads and asked the magazine to delete his records, but now wanted to know if he could be arrested, concluding that ‘there must be others like me in the same boat.'[1]

Conspiring Against Public Morals

Tony’s anxieties resulted from the prosecution of the underground newspaper International Times (IT), which began in 1969 and ended after a series of unsuccessful appeals in 1972. IT was the first countercultural magazine to include gay contact ads in a page of classifieds entitled ‘Males.’ These included several ads that later appeared to the police to be dubious, including the ‘Alert young designer, 30,’ seeking ‘warm, friendly, pretty boy under 23 who needs regular sex,’ and the ‘Genuine friend (versatile passive),’ looking for a man who ‘must be virile.’[2] How had IT come to grief for advertising what was, after 1967, a legal activity?

The answer lay in the particular history of conspiracy to corrupt public morals as a common law offence. In 1960, the Ladies Directory, a pamphlet advertising the services of prostitutes, had been prosecuted for that very offence, even though prostitution (though not soliciting it in public) was also a legal activity. Frederick Shaw, the publisher of the Ladies Directory, appealed to the House of Lords on the grounds that conspiracy to corrupt public morals was not an offence known to the law, merely a dangerous catch-all category in which the courts could retrospectively place any activity they deemed a public nuisance. Shaw lost his case, mainly because the Law Lords did recognise the existence of the offence, asserting that it originated in 1663. The Crown successfully argued at Shaw’s appeal that conspiracy to corrupt public morals was a single offence that grouped together particular kinds of immoral conduct over which the courts had long asserted jurisdiction. These were, primarily, obscenity, procuring prostitution, keeping a disorderly house, public indecency and public mischief. Although these could be offences in themselves, they could also be construed as conspiracies against morality where an agreement to do them had taken place. It was that interpretation of the common law which permitted the prosecution of Shaw for arranging what was a legal activity, and which was later used in a similar way against the underground press and gay men.

During Shaw’s appeal, Lord Reid, who had dissented to the majority view, nevertheless asserted that the law up to that point had recognised a category of ‘unlawful’ acts that might not be ‘breaches of the law at all, but which nevertheless are outrageously immoral or else in some way are extremely injurious to the public.’ This was the grey area into which male homosexuality descended after the decision in the IT appeal. During that case, Lord Reid argued that even though homosexuality between men was now legal in some senses, there was ‘a material difference between merely exempting certain conduct from criminal penalties and making it lawful in the full sense.’ The 1967 Sexual Offences Act, he argued, ‘enacts subject to limitation that a homosexual act in private shall not be an offence but it goes no farther than that . . . no licence is given to others to encourage the practice.’[3]

Free Speech and the Gay Press

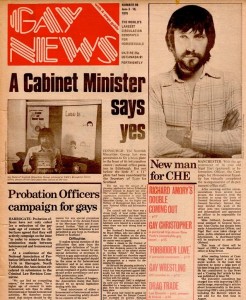

As Tony’s letter showed, many gay men recognised that this was a key setback, not only for those advertisers looking for love, but also for the freedom of the new gay press as a whole. For the campaigner Anthony Grey, who at the time was president of the Homosexual Law Reform Society, the IT case showed that the proponents of the 1967 Act had been too trusting. The key aim of gay life after 1967, as Grey recognised, was to put people in communication with each other in order to forge bonds of solidarity and community. A gay press was vital to that end. Free speech was therefore integral to the emergence of a gay civil society, and that issue was intimately bound up with the apparently trivial freedom to advertise for social activities, clubs, friends and sexual partners. The first editorial of Gay News in 1972 also saw the significance of the IT trial. ‘We feel that, despite legal reform and a certain relaxation in people’s attitudes to sexuality, that nothing much has really changed,’ the magazine lamented. It was clear ‘that many gay people are still extremely isolated, many still live restricted lives.’ The solution was ‘a medium which could help us all to know what we were all doing, which could put us in contact, and be open evidence of our existence and our rights for the rest of the people to see, [that ] could help start the beginning of the end of the present situation.’[4]

those advertisers looking for love, but also for the freedom of the new gay press as a whole. For the campaigner Anthony Grey, who at the time was president of the Homosexual Law Reform Society, the IT case showed that the proponents of the 1967 Act had been too trusting. The key aim of gay life after 1967, as Grey recognised, was to put people in communication with each other in order to forge bonds of solidarity and community. A gay press was vital to that end. Free speech was therefore integral to the emergence of a gay civil society, and that issue was intimately bound up with the apparently trivial freedom to advertise for social activities, clubs, friends and sexual partners. The first editorial of Gay News in 1972 also saw the significance of the IT trial. ‘We feel that, despite legal reform and a certain relaxation in people’s attitudes to sexuality, that nothing much has really changed,’ the magazine lamented. It was clear ‘that many gay people are still extremely isolated, many still live restricted lives.’ The solution was ‘a medium which could help us all to know what we were all doing, which could put us in contact, and be open evidence of our existence and our rights for the rest of the people to see, [that ] could help start the beginning of the end of the present situation.’[4]

An Establishment Backlash?

Was there an ‘Establishment backlash’ against the emerging gay community and its press? The legal situation of gay men was certainly precarious in the early 1970s. Between 1966 and 1974 the numbers of prosecutions for homosexual offences increased by fifty-five per cent, from 1553 to 2798 as police directed their attention to sex taking place in public and across the new age of consent boundary, while gay clubs and pubs were routinely subject to police harassment. Equally, in 1974 and 1975 there were a number of police raids on new gay magazines such as Him Exclusive that carried small ads and allegedly obscene material. However, the use of conspiracy against the gay press owed more to the fact that, following the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, gay men and women were eager to test the boundaries of public and private than to the existence of any secret Establishment cabal. It was widely recognised that this testing of the waters would follow the legislation envisaged by the Wolfenden Report of 1957, which had originally recommended decriminalising homosexuality between men.

To at least one observer, though, the use of the law of conspiracy against gay men had been fully justified. ‘Leaving aside any dispute about the power of judges to make what is in effect new law,’ the Sunday Telegraph commented in June 1972, ‘there will be general satisfaction that they have declared to be illegal any advertisement designed to put homosexuals in contact with one another.’ The problem was that gay people had not observed ‘the concept of privacy enshrined in the Wolfenden Act,’ which ‘should have applied, not only to homosexual practices as such, but to anything likely to encourage them.’ The 1967 Act, the Telegraph concluded, ‘was intended to protect an unfortunate minority from persecution, but not to empower them to spread their deviant ideas in society at large.’[5]

Harry Cocks is Associate Professor of History at Nottingham University. You can read his full discussion of ‘Conspiracy to corrupt public morals and the ‘unlawful’ status of homosexuality in Britain after 1967’ in Social History, 41:3, 267-284, at:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03071022.2016.1180899

References

[1] ‘Problems’, Jeffrey 2 (1973), 21

[2] National Archives, Kew, Director of Public Prosecutions, Case Papers, DPP 2/4670, Q v Knuller, Short Transcript, Monday 9th November 1970, 42, 43, 45.

[3] Shaw v DPP [1962] AC 220, 221, 273-4.

[4] Gay News 1 (1972), 2.

[5] ‘Gents Directory’, Sunday Telegraph 25th June 1972, 20.