I would like to respond briefly to Stefan Kirmse’s observations about “revisionism” among historians who wrote about the Soviet Union from the 1970s onward. I found myself in agreement with much of what he wrote but, as someone whose work has been characterized as “revisionist” and who has commented from time to time on these historiographic debates (most recently, in the Introduction and chapter one of Reflections on Stalinism, 2024), I am moved to add a few comments. First, to the extent that the term “revisionist” has any utility – and I agree with Kirmse that it has been overloaded with largely abusive allusions – it is to denote the contributions of those who, writing within the framework of political history, revised the master narrative of totalitarian control of society. The arch-revisionist, in my view, was the late J. Arch Getty. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Donald Filtzer, Wendy Goldman, myself and others are better understood as social historians. We did not necessarily analyze Soviet history from the bottom up, but we did not restrict ourselves to top-down analysis. Eventually, we engaged in many different points of entry – from the side, in the middle, regionally, sectorally, and so forth. Second, the heyday of social historical analysis in our field was somewhat foreshortened by the emergence of the subjectivity school associated with Jochen Hellbeck’s Revolution on My Mind (2006). Hellbeck challenged social history’s animus and conceptual frameworks by focusing not on collective social actors but individuals’ sense of “self” and their relationship to Soviet modernity. Third and finally, in recent decades, many self-identified social historians have absorbed and been engaged in applying a variety of different perspectives – from subjectivity to gender, ecology, migration, borderland studies, and political economy – while also expanding the chronological scope of their work. These developments have enriched understanding of the Stalin era (the focus of so much earlier work) by adding comparative dimensions with other countries as well as within the span of Soviet history. I thus agree with Stefan Kirmse that “revisionism,” along with “totalitarianism,” should be consigned to the dustbin of historiography. Lewis H. Siegelbaum is the Jack and Margaret Sweet Professor Emeritus of History at Michigan State University. He has published extensively on histories of Russia, Stalinism and life under Soviet rule. Continue reading

I would like to respond briefly to Stefan Kirmse’s observations about “revisionism” among historians who wrote about the Soviet Union from the 1970s onward. I found myself in agreement with much of what he wrote but, as someone whose work has been characterized as “revisionist” and who has commented from time to time on these historiographic debates (most recently, in the Introduction and chapter one of Reflections on Stalinism, 2024), I am moved to add a few comments. First, to the extent that the term “revisionist” has any utility – and I agree with Kirmse that it has been overloaded with largely abusive allusions – it is to denote the contributions of those who, writing within the framework of political history, revised the master narrative of totalitarian control of society. The arch-revisionist, in my view, was the late J. Arch Getty. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Donald Filtzer, Wendy Goldman, myself and others are better understood as social historians. We did not necessarily analyze Soviet history from the bottom up, but we did not restrict ourselves to top-down analysis. Eventually, we engaged in many different points of entry – from the side, in the middle, regionally, sectorally, and so forth. Second, the heyday of social historical analysis in our field was somewhat foreshortened by the emergence of the subjectivity school associated with Jochen Hellbeck’s Revolution on My Mind (2006). Hellbeck challenged social history’s animus and conceptual frameworks by focusing not on collective social actors but individuals’ sense of “self” and their relationship to Soviet modernity. Third and finally, in recent decades, many self-identified social historians have absorbed and been engaged in applying a variety of different perspectives – from subjectivity to gender, ecology, migration, borderland studies, and political economy – while also expanding the chronological scope of their work. These developments have enriched understanding of the Stalin era (the focus of so much earlier work) by adding comparative dimensions with other countries as well as within the span of Soviet history. I thus agree with Stefan Kirmse that “revisionism,” along with “totalitarianism,” should be consigned to the dustbin of historiography. Lewis H. Siegelbaum is the Jack and Margaret Sweet Professor Emeritus of History at Michigan State University. He has published extensively on histories of Russia, Stalinism and life under Soviet rule. Continue reading

A Response to Revision without ‘Revisionism’ by Lewis H. Siegelbaum

I would like to respond briefly to Stefan Kirmse’s observations about “revisionism” among historians who wrote about the Soviet Union from the 1970s onward. I found myself in agreement with much of what he wrote but, as someone whose work has been characterized as “revisionist” and who has commented from time to time on these historiographic debates (most recently, in the Introduction and chapter one of Reflections on Stalinism, 2024), I am moved to add a few comments. First, to the extent that the term “revisionist” has any utility – and I agree with Kirmse that it has been overloaded with largely abusive allusions – it is to denote the contributions of those who, writing within the framework of political history, revised the master narrative of totalitarian control of society. The arch-revisionist, in my view, was the late J. Arch Getty. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Donald Filtzer, Wendy Goldman, myself and others are better understood as social historians. We did not necessarily analyze Soviet history from the bottom up, but we did not restrict ourselves to top-down analysis. Eventually, we engaged in many different points of entry – from the side, in the middle, regionally, sectorally, and so forth. Second, the heyday of social historical analysis in our field was somewhat foreshortened by the emergence of the subjectivity school associated with Jochen Hellbeck’s Revolution on My Mind (2006). Hellbeck challenged social history’s animus and conceptual frameworks by focusing not on collective social actors but individuals’ sense of “self” and their relationship to Soviet modernity. Third and finally, in recent decades, many self-identified social historians have absorbed and been engaged in applying a variety of different perspectives – from subjectivity to gender, ecology, migration, borderland studies, and political economy – while also expanding the chronological scope of their work. These developments have enriched understanding of the Stalin era (the focus of so much earlier work) by adding comparative dimensions with other countries as well as within the span of Soviet history. I thus agree with Stefan Kirmse that “revisionism,” along with “totalitarianism,” should be consigned to the dustbin of historiography. Lewis H. Siegelbaum is the Jack and Margaret Sweet Professor Emeritus of History at Michigan State University. He has published extensively on histories of Russia, Stalinism and life under Soviet rule. Continue reading

I would like to respond briefly to Stefan Kirmse’s observations about “revisionism” among historians who wrote about the Soviet Union from the 1970s onward. I found myself in agreement with much of what he wrote but, as someone whose work has been characterized as “revisionist” and who has commented from time to time on these historiographic debates (most recently, in the Introduction and chapter one of Reflections on Stalinism, 2024), I am moved to add a few comments. First, to the extent that the term “revisionist” has any utility – and I agree with Kirmse that it has been overloaded with largely abusive allusions – it is to denote the contributions of those who, writing within the framework of political history, revised the master narrative of totalitarian control of society. The arch-revisionist, in my view, was the late J. Arch Getty. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Donald Filtzer, Wendy Goldman, myself and others are better understood as social historians. We did not necessarily analyze Soviet history from the bottom up, but we did not restrict ourselves to top-down analysis. Eventually, we engaged in many different points of entry – from the side, in the middle, regionally, sectorally, and so forth. Second, the heyday of social historical analysis in our field was somewhat foreshortened by the emergence of the subjectivity school associated with Jochen Hellbeck’s Revolution on My Mind (2006). Hellbeck challenged social history’s animus and conceptual frameworks by focusing not on collective social actors but individuals’ sense of “self” and their relationship to Soviet modernity. Third and finally, in recent decades, many self-identified social historians have absorbed and been engaged in applying a variety of different perspectives – from subjectivity to gender, ecology, migration, borderland studies, and political economy – while also expanding the chronological scope of their work. These developments have enriched understanding of the Stalin era (the focus of so much earlier work) by adding comparative dimensions with other countries as well as within the span of Soviet history. I thus agree with Stefan Kirmse that “revisionism,” along with “totalitarianism,” should be consigned to the dustbin of historiography. Lewis H. Siegelbaum is the Jack and Margaret Sweet Professor Emeritus of History at Michigan State University. He has published extensively on histories of Russia, Stalinism and life under Soviet rule. Continue reading

Informing an archivist in the post-Soviet space about your plans to work on the international ties of a Soviet republic often elicits a broadly similar response: raised eyebrows, shrugged shoulders, followed by a laconic comment that “it was all done by Moscow anyway.” Indeed, the classic narrative posits that the Soviet republics were Moscow’s pawns and had little agency of their own. That national identities were systematically repressed until at last, criticism of the Soviet system became possible under glasnost and perestroika. ‘Naturally’ this criticism came to be couched in national terms, and it was national mobilisation that led to, or at least dramatically accelerated, the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Informing an archivist in the post-Soviet space about your plans to work on the international ties of a Soviet republic often elicits a broadly similar response: raised eyebrows, shrugged shoulders, followed by a laconic comment that “it was all done by Moscow anyway.” Indeed, the classic narrative posits that the Soviet republics were Moscow’s pawns and had little agency of their own. That national identities were systematically repressed until at last, criticism of the Soviet system became possible under glasnost and perestroika. ‘Naturally’ this criticism came to be couched in national terms, and it was national mobilisation that led to, or at least dramatically accelerated, the collapse of the Soviet Union.  In recent years, approximately 72 million Europeans—representing 17% of the European Union’s population—have been classified as living in poverty. However, the current definitions of poverty have only been in use since the early 2000s. What, then, was the situation prior to that? Since when, and by what methods, has poverty been measured? What developments have taken place over the last century since the first conceptual frameworks emerged in Britain?

In recent years, approximately 72 million Europeans—representing 17% of the European Union’s population—have been classified as living in poverty. However, the current definitions of poverty have only been in use since the early 2000s. What, then, was the situation prior to that? Since when, and by what methods, has poverty been measured? What developments have taken place over the last century since the first conceptual frameworks emerged in Britain?  On 14 February 2025, I proudly defended my dissertation. After five years of wrestling with history, I was thrilled to have written a thesis that I could be proud of: The Lodging House and the City. Is this what it feels like to become a parent? Perhaps not entirely. I do not assume that new parents are asked if they perhaps like their baby too much. I was, when one of my jury-members asked if I had deliberately chosen the sacred day of Saint Valentine to declare my love for the lodging house as a bridgeway into questioning me on the rather optimistic narrative I had constructed. Had my “love” for the historical subject made me too blind to critically analyse it? Obviously, I had to disagree – I was there to defend, after all. But afterwards, it did trigger a reflection on how and why my research had pivoted in four years.

On 14 February 2025, I proudly defended my dissertation. After five years of wrestling with history, I was thrilled to have written a thesis that I could be proud of: The Lodging House and the City. Is this what it feels like to become a parent? Perhaps not entirely. I do not assume that new parents are asked if they perhaps like their baby too much. I was, when one of my jury-members asked if I had deliberately chosen the sacred day of Saint Valentine to declare my love for the lodging house as a bridgeway into questioning me on the rather optimistic narrative I had constructed. Had my “love” for the historical subject made me too blind to critically analyse it? Obviously, I had to disagree – I was there to defend, after all. But afterwards, it did trigger a reflection on how and why my research had pivoted in four years.  Out here in Jutland, the mainland peninsula of the Kingdom of Denmark, I live in something approaching a perfectly bureaucratic state. The people of my region, the Jutes, were once known for their non-conformity. Denmark’s national epic, Saxo’s Gesta Danorum from the early 1200s, calls the Jutes gens insolens “an uppity people”.[1] Another medieval chronicle of the late 1300s speaks of the antiquam Iutorum pertinaciam “the ancient obstinacy of the Jutes”.[2] Today, Jutes sometimes revel in their vestigial reputation for slyness and rule-bending. A popular euphemism for “cash-in-hand” in Danish literally means “Jutish dollars”. But for the most part this is an affectation. We are good subjects of the modern Danish welfare state. Like anywhere else in the country, we have a rule and a correct process for nearly every occasion. Francis Fukuyama has made a career out of being awe-inspiringly mistaken about the arc of history, but he was not totally wrong to make “Denmark” a euphemism for a well-ordered society.[3] At the university where I work a sacred (and to me, I admit, impenetrable) website called the studieordning regulates all aspects of assessment, curriculum and examination in minute detail. A two-step authentication app on my smartphone, called MitID, is required for everything from booking dentists’ appointments to paying my credit card bill. Woe betide any member of my local sauna and wild swimming club who has not kept themselves appraised of the thirty-odd vedtægter (rules). You can be naked, but you can never strip off the law. Some of my research into the history of bureaucracy in Denmark has recently been published in Social History – namely, an article on those who lived out my own fantasy of burning piles of paperwork during the Danish Peasants’ Revolt of 1438-1441.

Out here in Jutland, the mainland peninsula of the Kingdom of Denmark, I live in something approaching a perfectly bureaucratic state. The people of my region, the Jutes, were once known for their non-conformity. Denmark’s national epic, Saxo’s Gesta Danorum from the early 1200s, calls the Jutes gens insolens “an uppity people”.[1] Another medieval chronicle of the late 1300s speaks of the antiquam Iutorum pertinaciam “the ancient obstinacy of the Jutes”.[2] Today, Jutes sometimes revel in their vestigial reputation for slyness and rule-bending. A popular euphemism for “cash-in-hand” in Danish literally means “Jutish dollars”. But for the most part this is an affectation. We are good subjects of the modern Danish welfare state. Like anywhere else in the country, we have a rule and a correct process for nearly every occasion. Francis Fukuyama has made a career out of being awe-inspiringly mistaken about the arc of history, but he was not totally wrong to make “Denmark” a euphemism for a well-ordered society.[3] At the university where I work a sacred (and to me, I admit, impenetrable) website called the studieordning regulates all aspects of assessment, curriculum and examination in minute detail. A two-step authentication app on my smartphone, called MitID, is required for everything from booking dentists’ appointments to paying my credit card bill. Woe betide any member of my local sauna and wild swimming club who has not kept themselves appraised of the thirty-odd vedtægter (rules). You can be naked, but you can never strip off the law. Some of my research into the history of bureaucracy in Denmark has recently been published in Social History – namely, an article on those who lived out my own fantasy of burning piles of paperwork during the Danish Peasants’ Revolt of 1438-1441.  Pleasure has been the subject of intense debate across history and became a particularly important part of discourse in the eighteenth century. This blog argues that amidst the many and varied pleasures of the public sphere, elite men and women laid claim to the family and family relations as the most enduring and pleasurable of pleasures.

Pleasure has been the subject of intense debate across history and became a particularly important part of discourse in the eighteenth century. This blog argues that amidst the many and varied pleasures of the public sphere, elite men and women laid claim to the family and family relations as the most enduring and pleasurable of pleasures.  The aim to highlight marginalised voices is nowadays a standard feature in historical research. While bringing these voices to the fore will continue to be important, I have become increasingly intrigued by the group of people caught between the marginalising power holders and the marginalised. In other words, I have become interested in the middle ground, history from the middle rather than history from below. My recent article in Social History considers this overlooked category in relation to the specific Finnish context of correctional labour facilities.

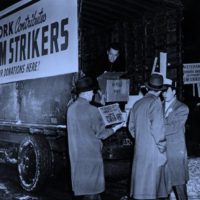

The aim to highlight marginalised voices is nowadays a standard feature in historical research. While bringing these voices to the fore will continue to be important, I have become increasingly intrigued by the group of people caught between the marginalising power holders and the marginalised. In other words, I have become interested in the middle ground, history from the middle rather than history from below. My recent article in Social History considers this overlooked category in relation to the specific Finnish context of correctional labour facilities.  In 2023, a six-week strike by the United Auto Workers led to major wage and benefit gains for workers at America’s “Big Three” car makers – General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. The strike received widespread public attention, with a Gallup poll showing that 75 percent of Americans supported the UAW in its fight for higher pay and more job security.[1] In September, President Biden even walked the UAW’s picket line in Belleville, Michigan, the first sitting U.S. president to join a picket line. “Unions built the middle-class,” he asserted. “That’s a fact.”[2] Biden’s action reminds us that strikes – a unique expression of citizens’ frustration – matter. In particular, the 2023 walkout showed the ability of big auto strikes to capture broader attention. BBC News, The Guardian, and Reuters were among those there, seeing the dispute as integral to a broader upsurge in labour activism that was linked to the rising cost of living, a tight labor market, and wage stagnation. Overall, 2023 would witness a “hot labor summer” of strikes in the U.S., the number of walkouts reaching levels not seen in decades.[3] In the wake of the pandemic, there were similar trends elsewhere; in 2022, the number of working days lost to strikes in the UK rose to the highest level in over a decade, while the EU Observer reported a “new surge of industrial action” across Europe.[4] In particular, there are parallels with a huge strike at General Motors (GM) in 1945-46. Part of my wider research on the U.S. auto industry, this article was completed as the 2023 strike unfolded. Both were important events that were led by the UAW, an 88-year old organization that was for decades America’s biggest industrial union.[5]

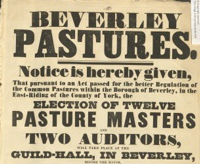

In 2023, a six-week strike by the United Auto Workers led to major wage and benefit gains for workers at America’s “Big Three” car makers – General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. The strike received widespread public attention, with a Gallup poll showing that 75 percent of Americans supported the UAW in its fight for higher pay and more job security.[1] In September, President Biden even walked the UAW’s picket line in Belleville, Michigan, the first sitting U.S. president to join a picket line. “Unions built the middle-class,” he asserted. “That’s a fact.”[2] Biden’s action reminds us that strikes – a unique expression of citizens’ frustration – matter. In particular, the 2023 walkout showed the ability of big auto strikes to capture broader attention. BBC News, The Guardian, and Reuters were among those there, seeing the dispute as integral to a broader upsurge in labour activism that was linked to the rising cost of living, a tight labor market, and wage stagnation. Overall, 2023 would witness a “hot labor summer” of strikes in the U.S., the number of walkouts reaching levels not seen in decades.[3] In the wake of the pandemic, there were similar trends elsewhere; in 2022, the number of working days lost to strikes in the UK rose to the highest level in over a decade, while the EU Observer reported a “new surge of industrial action” across Europe.[4] In particular, there are parallels with a huge strike at General Motors (GM) in 1945-46. Part of my wider research on the U.S. auto industry, this article was completed as the 2023 strike unfolded. Both were important events that were led by the UAW, an 88-year old organization that was for decades America’s biggest industrial union.[5]  In the 1830s, towns in England and Wales went through a series of dramatic changes of governance. Two were driven by famous pieces of legislation: the 1832 Reform Act, which reconstructed urban Parliamentary franchises; and the 1835 Municipal Corporations Act, which recast civic government. The third was the significant reorganisation of civic space and property rights, which followed as an unintended consequence of these Acts. My recent Social History article shows that by changing who was represented, and how civic government was constructed in over 100 towns and boroughs, these acts restructured freemen’s (and their widows’) rights to corporate property, sometimes extinguishing rights to urban lands that had been possessed in common for centuries, and sometimes recasting the complicated political relationships that had grown up around these rights.[1]

In the 1830s, towns in England and Wales went through a series of dramatic changes of governance. Two were driven by famous pieces of legislation: the 1832 Reform Act, which reconstructed urban Parliamentary franchises; and the 1835 Municipal Corporations Act, which recast civic government. The third was the significant reorganisation of civic space and property rights, which followed as an unintended consequence of these Acts. My recent Social History article shows that by changing who was represented, and how civic government was constructed in over 100 towns and boroughs, these acts restructured freemen’s (and their widows’) rights to corporate property, sometimes extinguishing rights to urban lands that had been possessed in common for centuries, and sometimes recasting the complicated political relationships that had grown up around these rights.[1]  Workhouses, and the poor who inhabited them, continue to fascinate us all. From social historians to the wider public, we are intrigued by the institution and the characters within. As I explore in a recent article for Social History, those who spent their old age in poverty under the Victorian New Poor Law regime did not always face a one-way route to the workhouse. In fact, the Board of Guardians provided welfare to those in their own homes if they successfully applied for outdoor relief. Before the introduction of old age pensions in 1908, there was no guarantee that one would receive welfare when they reached old age; one had to actively apply to the Board of Guardians for outdoor relief. The Board of Guardians thought older people were the ‘most deserving’ recipients of welfare, compared with the ‘able-bodied’, or ‘working-age’, population, owing to their perceived infirmity.

Workhouses, and the poor who inhabited them, continue to fascinate us all. From social historians to the wider public, we are intrigued by the institution and the characters within. As I explore in a recent article for Social History, those who spent their old age in poverty under the Victorian New Poor Law regime did not always face a one-way route to the workhouse. In fact, the Board of Guardians provided welfare to those in their own homes if they successfully applied for outdoor relief. Before the introduction of old age pensions in 1908, there was no guarantee that one would receive welfare when they reached old age; one had to actively apply to the Board of Guardians for outdoor relief. The Board of Guardians thought older people were the ‘most deserving’ recipients of welfare, compared with the ‘able-bodied’, or ‘working-age’, population, owing to their perceived infirmity.