Listening to a History Extra podcast recently (this is what historians do on their days off!), I was struck by the truism reiterated by one of the contributors that all historical writing is to some extent autobiographical.[1] Our beliefs, lives and world view inevitably seep into the work we produce. This led me to reflect on the genesis of my piece (on the early labour movement’s turncoats and traitors) in the latest issue of Social History and on the mainspring of three earlier articles on different aspects of working-class leadership and agitational activity in reform-era Yorkshire. All four studies focus on the lesser-known local leaders of working-class agitations rather than their more famous, often metropolitan or gentlemanly, figureheads, thereby raising questions about why my research interests have tended to skew towards the undercard rather than the main protagonists of historical investigation.

Turncoats and Footnotes

The turncoat article, for example, examines the careers of two West Riding leaders of the 1820s and 1830s, John Tester and George Beaumont, or at least the fragments that have come down to us via the historical record. Tester, a woolcomber, was the young leader of one of the bitterest and most influential industrial conflicts of the pre-Victorian period: ‘The Great [Bradford] Strike of 1825’.[2] The ever-combative Beaumont, a fancy weaver from Almondbury, a radical hotbed outside Huddersfield, was active in the political, factory reform and trades’ union campaigns of the early 1830s.

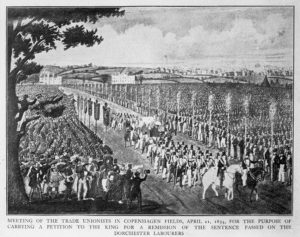

Both ‘turned coat’ and were enlisted in the cause of anti-trades’ unionism in the pivotal year of 1834: the highpoint of general unionism and the brief incandescence of that famous forerunner of the TUC, the Grand National Consolidated Trades’ Union (GNCTU). It was also the date of the corresponding government-led response, personified in the prosecution and transportation of the ‘Dorchester [Tolpuddle] labourers’. The study argues that much can be learnt about both the fragility and the resilience of early working-class movements by exploring the careers of the villains as well as the heroes of labour history.[3]

Some of these local stalwarts featured prominently in my preceding studies. The Northern History article, for example, examined how local politics in many West Riding textile communities was animated by a cadre of accomplished and assertive working-class leaders. Another study published in the Labour History Review sought to reappraise the significance of largely forgotten trade union leaders such as Bradford-based John Douthwaite, a former colleague of John Tester and one of five members of the Executive Committee of the GNCTU. A third piece, in the History Workshop Journal, proposed a typology for analysing local leadership, explored the pleasures and pains of being a prophet in your own land and examined how local leaders sat within their host communities and both drew on and contributed to its cultural wealth.[4]

Some clues as to the origins of this recurring interest in routes less travelled and leaders less well-known can be found buried in the footnotes of the Social History piece and in the very title of the History Workshop Journal article. The conclusion to the ‘turncoats and traitors’ piece makes reference to a couple of unusual sources: Tony Collins’ excellent study of the social history of rugby league and Paul Cooke’s ghosted autobiography.[5] These are used to note how leaders can be revered but also still form an integral part of their local community, and to illustrate the very real, but time-limited and provisional nature of their eminence. A third, short but influential source (on the transitory nature of fame) could not be shoehorned in: a brief entry by Raymond Fletcher, in Michael Ulyatt and Bill Dalton’s centenary account of the most memorable derby matches between Hull FC and Hull Kingston Rovers. Later renowned as a journalist and statistician of the game, Fletcher (then a nine-year old boy) recalled that the 1950 Good Friday derby was ‘embossed in my mind for just one reason – a reserve team winger called Sanders scored all three tries for Hull in a 15-6 win [in front of 18,000 people] at the Boulevard’. Indeed, ‘Sanders caused a bit of a sensation with his hat-trick’.[6] Forty years on from the event, he had described my dad’s finest sporting hour: a dose of deferred fame that the latter received with a mixture of pride, pleasure and bemusement.

My dad, a lifelong fan, had signed for Hull in 1947 (ironically after a three-match trial with Rovers didn’t result in an acceptable signing-on fee). He went on to have an intermittent career with Hull, playing occasionally for the first team, but mainly for the ‘A’ (reserve) team. His opportunities were limited by the signing of two Australian ‘star’ wingers and not helped by the fact that he had started his rugby career late, at the age of twenty-eight, due to military service in the Second World War.

Never a bitter man, my dad accepted what chances came his way. Indeed, he actively sought out his Australian nemeses when he temporarily emigrated later in life. But I always suspected that, though flattered that his finest hour had been commemorated in print, he was slightly irked by the title that Raymond Fletcher chose for his piece: ‘Into Obscurity’, and itched to provide more historical context to augment the journalist’s brief account. As my father recalled years later, the really interesting part of the story (and the reason that he hadn’t been able to build on his moment of glory) was that the victorious Hull players who had recently joined an innovative players’ union, had all gone on strike immediately after the game, because of the Hull Board’s refusal to pay the promised winning ‘special bonus’. The players initially remained solid but were all banned by the club, and replaced with reserves for subsequent matches.

‘Into obscurity’ entered the family’s folklore and became its de facto ironic motto. So much so that when my father died in 2006 his life was celebrated under the heading: ‘Out of obscurity’; and I subsequently drew on this inverted dictum for the title of my History Workshop Journal article exploring the contribution of local leadership cadres to the vitality of early working-class movements.

Increasingly, I recognise that my dad’s sporting experience, and the political activities of his own father, a dustman turned ambulance driver, who served as Labour Party agent for his local ward in the 1920s, have perhaps unwittingly made me more sensitive to the contributions of the team players and the background organisers who underpinned early radical campaigns and often kept nascent movements alive. Unsurprisingly, fragments of the lives of over a hundred of such figures feature prominently in my forthcoming book on leadership and organisation of early working-class movements in the West Riding textile district.[7]

The Past, the Present and the Personal

Reflecting on my own experience of returning to academic writing (as an independent scholar) late in life I am often reminded of how often history interacts with present or recent past and the personal. This hit home recently when investigating the life of John Hanson: Huddersfield radical, factory reformer, Owenite socialist, invalid and polymath. This research was given a fillip by finally solving the mystery of a cryptic phrase in Hanson’s brief newspaper obituary that after being ‘a small shopkeeper in Liverpool, [he] then gravitated into West Derby Union’.[8] The penny finally dropped a couple of months ago that ‘West Derby’ was not a district of the Derbyshire town (now city), but the suburb of Liverpool that I travel though at least once a week. The West Derby [Poor Law] Union had indeed built a workhouse there between 1864 and 1869. This later became Walton Hospital where my sister-in-law worked for twenty years. And sure enough there is a John Hanson in the archives of Walton Workhouse in 1868 and also in Mill Road Hospital, closer to Liverpool town centre (also a workhouse and part of the West Derby Union). The 1871 census records John Hanson, b. 1791, birth county Yorkshire, as an ‘Inmate’ of West Derby Workhouse, Walton on the Hill, a poignant location for a virulent opponent of the new poor law in the 1830s. The past is often close and is sometimes personal.

If, in E. H. Carr’s words, history is ‘an unending dialogue between past and present’; it is also an intermittent conversation between the personal and the generic and between the particular and the universal.[9] TV producers and best-selling historians have long-since discovered the power of family history and biography as a means of linking these poles. More recently, in a posthumous article, Malcolm Chase proposed a ‘biographical turn’ in labour history to sharpen its focus on lived experience.[10] This plea reiterated the power of individual stories to reveal the nuances and idiosyncrasies of human endeavour and served as a reminder that people are present at the making of their own history. Whilst it is necessary to be aware of the extent to which our personality, preoccupations and prejudices impact on the narrative and analysis that we present, it is also important to recognise the value of the personal or familial in helping us interrogate evidence, make sense of the past and articulate its significance to a wider audience.

One of the lesser-known unintended consequences of the Covid lockdown was the opportunity it gave me to revisit academic research I had originally engaged in during the 1970s and early 1980s – before and during the arrival of children and the need to ‘get a proper job’! My subsequent employment in various sectors of adult, further, and higher education, including 30 years as an Open University Associate Lecturer, gave little opportunity for historical writing, though I did co-author reports and published articles on various aspects of adult learning, widening participation, and teaching excellence. Since retiring I have returned to writing about football on the Football Paradise website, and history (as outlined in the blog). My current research explores popular radicalism and music in the early Victorian era through the life and times of John Hanson, Huddersfield radical, Owenite socialist and factory reformer.

References

[1] History Extra podcast ‘Eastern Europe: a personal journey through the region’s past’, 17 July 2023, available at: https://www.historyextra.com/period/general-history/eastern-europe-podcast-jacob-mikanowski/ accessed 27 August 2023.

[2] W. Scruton, ‘The Great Strike of 1825’, Bradford Antiquary, 1 (1888), 67-73.

[3] J. Sanders, ‘Turncoats and traitors, rogues and renegades: reviewing labour’s lost leaders in reform era Yorkshire’, Social History, 48, 3 (2023)

[4] J. Sanders, ‘The Voice of the “Shoeless, Shirtless and Shameless”: Community radicalism in the West Riding, 1829 to 1839’, Northern History, 58, 2 (2021), 265-6; J. Sanders, ‘John Douthwaite and “John Powlett”: Trades’ Unionism and Conflict in Early 1830s Yorkshire’, Labour History Review, 86, 1 (2022), 8-17; J. Sanders, ‘Out of Obscurity: Local Leadership and Cultural Wealth in the Radical Communities of the West Riding Textile District, 1825-40’, History Workshop Journal, 94 (2022), 1-23.

[5] T. Collins, Rugby League in Twentieth Century Britain: A social and cultural history (London, 2006); P. Cooke and A. Durham, Judas? The story of Paul Cooke (Worthing, 2016).

[6] M. E. Ulyatt and B. Dalton, Hull – A Divided City: Rugby League matches Between Hull Kingston Rovers and Hull Football Club, 1899-1989 (Beverley, 1989), 23.

[7] J. Sanders, Workers of Their Own Emancipation: Working-class leadership and organisation in the West Riding textile district, 1829-1839 (London, forthcoming)

[8] Huddersfield Daily Chronicle 19 January 1878, 8.

[9] E. H. Carr, What is History? (Harmondsworth, 1968 edn), 30

[10] M. Chase, ‘Labour History’s Biographical Turn’, History Workshop Journal, 92 (2021), 194-207.