The conventional image of an entrepreneur in Victorian Britain is a captain of industry, heading  an engineering or steel factory employing hundreds of workers, and generally pictured with an impressive moustache. But men like that were only the tip of a very large, and much more diverse entrepreneurial iceberg. My research shows that close to 30% of businesses in Victorian Britain were run by women, a proportion that was much larger than hitherto estimated. This work is based on the new British Business Census of Entrepreneurs, created at the University of Cambridge as part of the project ‘Drivers of Entrepreneurship’ under Professor Robert Bennett.

an engineering or steel factory employing hundreds of workers, and generally pictured with an impressive moustache. But men like that were only the tip of a very large, and much more diverse entrepreneurial iceberg. My research shows that close to 30% of businesses in Victorian Britain were run by women, a proportion that was much larger than hitherto estimated. This work is based on the new British Business Census of Entrepreneurs, created at the University of Cambridge as part of the project ‘Drivers of Entrepreneurship’ under Professor Robert Bennett.

This database contains an extraction and reconstruction of the whole business population of England, Wales and Scotland between 1851 and 1911, deposited with the UK Data Archive. As the project’s findings, presented in The Age of Entrepreneurship (2019), have revealed, despite the enduring image of the large-scale business as synonymous with this historical moment, the Victorian period was a golden age for smaller and medium-sized enterprises.

Women entrepreneurs, then and now

The project has also exposed the gender nuances of these small businesses, a subject which forms the focus of a recent Social History article ‘Female entrepreneurship: business, marriage and motherhood in England and Wales, 1851–1911’. The findings show that women formed a sizable part of the business population in this period, owning 27-30% of all businesses between 1851 and 1911. This is considerably higher than current figures: statistics from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy shows that 21% of businesses were female-led in 2017.[1]

While nowadays the sectors with the highest proportions of female involvement include education and the health services, where women constitute 50% of proprietors, in Victorian Britain the most female-dominated sectors were clothing manufacturing and personal services. In 2017, manufacturing was one of the lowest sectors for female business participation at 12%, the same proportion as it was in 1901. While many Victorian manufacturing businesses ran by women were related to the textile industry, there were also many women running more traditionally masculine trades, such as Eliza Tinsley, who in 1871 owned a nail and chain manufacturing firm in Dudley, Staffordshire, employing 4,000 people.

Women in Business

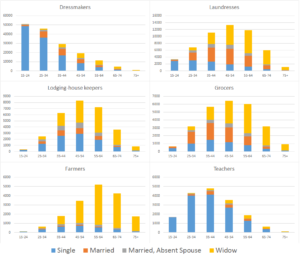

Eliza Tinsley’s involvement in heavy manufacturing was relatively unusual in more male-dominated sectors such as construction, mining and transport, but women entrepreneurs were conspicuous in other economic activities. Figure 1 shows the age and marital status profiles for female entrepreneurs in some of the key occupations in which women ran businesses: dressmaking, laundry, lodging-house keeping, grocers, farming, and teaching. These six occupations together account for over 60 per cent of all female entrepreneurs in 1901, a typical year.

Figure 1. Age and marital status for six key female sectors in England and Wales, 1901. Source: BBCE.

The figure shows that the female entrepreneur didn’t exist: differences between the sectors were stark, in both age and marital status. Dressmaking stood out as an occupation that allowed women to run their own business from a young age. Most other occupations featured a more gradual build-up with small numbers of entrepreneurs at a younger age, peaking in middle age and then declining. The largest groups of laundry proprietors, lodging-house keepers, and grocers were between 45 and 54, with farmers skewed towards slightly older women and teachers skewed towards younger women.

The impact of marriage and motherhood

Marital status patterns varied considerably as well. While demographic trends influenced age and marital status patterns, with younger women more likely to be single and older women more likely to be widowed, there were clear differences between the sectors. Both dressmakers and teachers stand out as least likely to marry, even in the higher age groups. Farmers, on the other hand, were very often widows even at a young age. Very few lodging-house keepers were married with a husband living with them at home, with the majority either single, widowed, or married with an absent husband. Only laundresses and grocers were likely to be married women running their own businesses, with the majority of entrepreneurs between the ages of 35 and 44 married and living with their husband.

‘Co-preneurship’ and ‘mumpreneurs’ played a similarly important role in Victorian Britain as they do today. While many women dropped out of the formal labour force after marriage and childbirth, for those who remained economically active entrepreneurship was an attractive option. While roughly similar proportions of economically active single men and women ran their own businesses, after marriage, economically active women were overall more likely than men to be business proprietors. In some cases, married women ran a business in partnership with their spouse, a common dynamic for grocers, for example. But in the majority of married female entrepreneurs’ households, the wife ran a business while her husband was a wage labourer, which was a common dynamic for laundresses and dressmakers.

Having young children increased the likelihood of running a business as well: mothers’ entrepreneurship rates increased with the arrival of one child and continued to increase the more children under 5 years old were added to a household. The underlying drivers of entrepreneurship in such cases were a combination of social and legal restrictions on female wage labour participation, the increased flexibility in terms of working hours, and being able to work from home (which over 70% of female business owners, but only 7% of workers was able to do). Neither marriage nor motherhood, therefore, prohibited women’s entrepreneurial prowess.

Conclusions

The British Business Census of Entrepreneurs will allow business historians to study the full population of entrepreneurs, including those who employed others and the self-employed. This will allow new insights into who ran what type of business and challenge the perception on what it meant to be a business proprietor in Victorian and Edwardian Britain. As this brief discussion has outlined, the database will also change our historical presumptions about women’s supposed marginalisation in business enterprise. Female entrepreneurial activity continues to be shaped by life-cycle events such as motherhood and historical understanding of women’s access to business and why they were attracted to specific occupational sectors has much to tells us about the entrepreneurial choices which govern women in the twenty-first century as well as in the past.

Carry van Lieshout is a Post-Doctoral Research Associate at the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure at the University of Cambridge. She is a socio-economic historian with interests in gender, entrepreneurship and environmental history. Her co-authored article ‘Female entrepreneurship: business, marriage and motherhood in England and Wales, 1851–1911’ features in Social History 44,4 and is available to read online.

References

[1] C. Rhodes, Business Statistics, Briefing Paper No.06152, 12 December 2018, p. 10.