On 14 February 2025, I proudly defended my dissertation. After five years of wrestling with history, I was thrilled to have written a thesis that I could be proud of: The Lodging House and the City. Is this what it feels like to become a parent? Perhaps not entirely. I do not assume that new parents are asked if they perhaps like their baby too much. I was, when one of my jury-members asked if I had deliberately chosen the sacred day of Saint Valentine to declare my love for the lodging house as a bridgeway into questioning me on the rather optimistic narrative I had constructed. Had my “love” for the historical subject made me too blind to critically analyse it? Obviously, I had to disagree – I was there to defend, after all. But afterwards, it did trigger a reflection on how and why my research had pivoted in four years.

On the origins of my research: from infrastructure to people

I started working on the history of lodging houses in nineteenth-century Antwerp in late 2020. Having just obtained my Master’s degree with a thesis on negotiating sovereignty through tram infrastructure in Qing-China, I was ready for a new direction. Ironically, although my case-study had migrated halfway across the globe, much of my thinking had actually remained in place. I inherited this perspective from my thesis (and later PhD co-supervisor) Greet De Block. And, similar to my thesis, I initially approached lodging houses as a kind of infrastructure: a migration/arrival infrastructure.[1] From this perspective, the Antwerp lodging house was, like the tram in China, interrogated for how it affected urbanites’ behaviours. Eagerly, I delved into police reports and city directories to reconstruct Antwerp’s lodging landscape, which shaped up to become my first publication on the subject. Central research questions at this stage were oriented at understanding the process of arrival, and how lodging infrastructures shaped and channelled newcomers’ experiences.

By the end of the first year, my perspective had started to shift. I had dropped the infrastructural focus from conference paper titles, although it still featured in historiographical discussions. Rather, I now approached my research consistently from a more methodological and conceptual angle, that of “floating populations”. Having finally read up more on migration historiography, I had grown interested in the ways that general migration sources over- and undervalued particular types of movement. Migration in nineteenth century cities was, I learned, by a large degree characterised by “floating populations” of transmigrants, sailors, merchants, seasonal workers, sex workers, and the like, who, because of their often temporary stay, had largely avoided the historian’s gaze. The position of my subject, the lodging infrastructure, had fundamentally changed in my research from a study in its own right, to a methodological tool, a lens.

Looking for lodgers and finding housekeepers

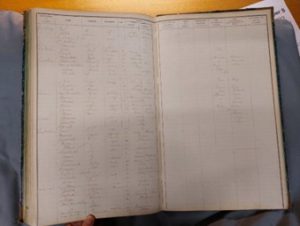

I had been pushed in this direction at two fronts. First, a major influence at this point was Leo Lucassen’s chapter A Blind Spot, where he argues that the historiographical neglect of itinerant groups was not only to be blamed on documenting and preserving processes, but on historians too. Social historians, Lucassen argues, had shown little interest in non-regular, non-waged labour, following Marx’s characterisation of such groups as the “Lumpenproletariat”: workers unable to achieve class consciousness, and thus an uninteresting category of historical analysis.[2] Second, I had found 28 immense volumes of so-called lodging registers in the Antwerp archives. These registers contained thousands and thousands of entries of lodgers and hotel guests per year, featuring exactly the groups which historians had ignored (see below).

Tackling this exciting source, however, created new difficulties that I did not anticipate. It was unclear how and why the source was actually constructed. Although much exciting research had appeared on documenting migrants in Belgium and in Antwerp recently, the lodging register seemed to fly somewhat under the radar. To understand these sources, I had gotten in touch with Torsten Feys, an expert on Belgian migration control. Together with my supervisor, Hilde Greefs, and a friend of Torsten’s, Kevin James, we organised a two-day workshop tracing the genealogy of lodging registers across Europe.

Co-organising this workshop had two unintended consequences. First, it became clear that simply understanding how the source was constructed had sneakily and gradually spiralled into a research project on its own. A project that dealt with questions of bureaucratisation, statecraft, and registration. Third, my growing preoccupation with how information was produced brought me directly to the lodging housekeepers themselves. Understanding the lodging register, then, required understanding the housekeeper too.

Looking into lodging housekeepers took me deepest into the subject I had been thus far. I was reading up on social histories, particularly those interested in work and domesticity, again looking beyond those heavy industries that Marx had put on historians’ agendas. In my own research, I took a deep dive into lifecourses and strategies of housekeepers, initially to understand their role in documentation practices, but soon, to understand how they structured their daily lives. The fruits of this research can be found in the latest issue of Social History. Around this time too, I garnered a certain aversion to the concepts that had inspired me early on. Listening to the lives, trials and tribulations of lodging housekeepers made it difficult for me to refer to the environments that they built as infrastructures – a concept which now felt dehumanising and distant. As readers can see, I nearly abandoned the concept altogether in my Social History article.

Becoming a Lodging House Guy

At this stage, I was struggling a lot to come to grips with the changing outline of my project. While the individual pieces – on lodging landscapes, documentation practices, and housekeepers – were landing on their feet, it became more difficult to see the forest through the trees. As I continued to present on these topics at academic events, I continuously got asked where I wanted to take this project. Was this a project on understanding the lives of itinerant groups through the lodging house, or was this a project on understanding lodging houses, with itinerant groups as one of the aspects to be studied? This question became most explicit during a Masterclass with Tim Hitchcock at the European Association for Urban History Conference in September 2022. In the discussion I stated that I wanted to be a migration historian, not a lodging house historian. After all, I could count the number of historians interested in lodging houses on one hand. I was anxious that writing a dissertation on lodging houses would render me an obscure monomaniac: a “lodging house guy”.

In retrospect, I probably already was a “lodging house guy” at that point, although I still would have to come clean. Colleagues helped me finding myself in this process by gifting me a mug for my birthday. My earlier hesitations to turn straight to the lodgers themselves, instead of seeking to first understand the urban landscape, the documentation practices, and later the housekeepers, were indicative of a larger hesitation to use the lodging house as a lens on itinerant groups. For this, the lens in itself seemed too big of a black box, and too great a factor in potentially skewing my results, something also noted during the Masterclass.

To explain this attitude, I often draw comparisons with the early modern guild. Not only is this thematically relevant – lodging houses played a major role in structuring migrant labour after the formal breakdown of guilds – but also on a metahistorical level. Although sources deriving from guilds have taught us much about the Early Modern period’s themes as diverse as work, migration, social mobility, craftsmanship and politics, such works would have been impossible without first understanding the mechanics that tick the institution of the guild. I found that the same applied for lodging houses. Ultimately, I wrote a chapter on lodgers too, but undoubtedly I perhaps could have covered more ground in understanding their histories, had my research not pivoted so much.

Serendipity and the transformation of historical research

At my defence, another member of the jury asked why I had moved away from infrastructure as a guiding concept, something that had structured much of my early work. He emphasised that current migration sociologists emphasise the dynamism and fragility of infrastructure, exactly the reasons I had turned away from the concept. It was a fair question, and in a sense, it brought my journey full circle. Infrastructure had been useful: it gave me a language to think about lodging houses as a framework of mobility. But as I spent more time peeking into these diverse spaces, the concept of infrastructure began to feel almost too clean, too abstract, and too distant. In its place came the messiness of history.

I hope to have shown that my pivot from infrastructure to lodgers to lodging houses, and perhaps more broadly, from concepts to histories, happened largely through chance encounters and – if I may be so blunt – sleepwalking through spiralling side quests. I hope this blog post offers some clarifications, to my jury, maybe, but also more broadly, to historians grappling with changing projects, ideas, and identities. It is important that we as historians continue to communicate how and why our ideas evolve through project lifecycles, instead of merely signposting the result. With my dissertation defended, I am done with lodging houses, for now. But are lodging houses done with me? I might revisit them in the (near) future, with another identity, I might not. After all, what good would any historian be, if they never changed their mind? And while I may not have chosen Valentine’s Day as a deliberate ode to lodging houses, I suppose it fits well. I am, after all, a lodging house guy.

Jasper Segerink is senior researcher at the Centre for Urban History (University of Antwerp) and at the YUFE-alliance. There, he continues his work and teaching from an interdisciplinary perspective, now focussing on the social histories of railway neighbourhoods.

References

[1] Meeus, Bruno, Karel Arnaut, and Bas van Heur, eds. Arrival Infrastructures. Migration and Urban Social Mobilities. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

[2] Lucassen, Leo. “A Blind Spot: Migratory and Travelling Groups in Western European Historiography.” International Review of Social History 38, no. 2 (August 1993): 209–35.