Additions to the Western lexicon

Hipster (1941): someone who is ‘Hip’ or in touch with the fashion.

Hipster (1941): someone who is ‘Hip’ or in touch with the fashion.

Hippy (1953): originally Hipster (1941) was used but then ‘Hippy’ became the term to use in the 1960s to denote West Coast American youth rejecting conventional society.

Flower Children/Flower People (1967): alternative name for Hippies. see above.

Freak (1967): Someone who freaks out on drugs

Generation Gap (1967): Difference in outlook between older and younger people.

Groupie (1967): a young female fan of rock group.

‘Love In’/‘Be-In’ (1967) : communal acts usually by students.

‘Straight’ (1967): Someone who conforms to conventions of society.

Vibes (1967): instinctive feelings.

Source: John Ayto 20th Century Words (Oxford, 1999).

This year, 2017, will witness the fiftieth anniversary of what subsequently became known as the ‘Summer of Love.’[1] One of its legacies as can be seen above, was to add to the Western lexicon. Indeed, 1967 was the year in which the counterculture became ‘visible’ in Western society and the underground came up for air. This was to be the year of the ‘hippies,’ or the ‘flower children’ as they were also known. Hippies were predominantly middle-class youths (usually under 25 years of age) and flower power was born on west coast USA, especially the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco. Hippies embraced what became known as the counterculture which moved across the Atlantic and, subsequently, made an impact in Britain and Europe. Hippiedom was the product of post-war affluence and, given its class profile was particularly well represented on the university campus. The counterculture had gathered momentum from at least 1964, if not before, for that was the year of publication of Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert’s book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based of the Tibetan Book of The Dead.(1964) It was also the year that Herbert Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man was published, which was a key text of the New Left. The central motto of Marcuse’s book was that ‘One dimensional man has lost, or is losing individuality, freedom; the ability to control one’s own destiny.’ This idea partly underpinned the student protest of the later 1960s on the university campuses, where students felt they were simply being processed for the needs of the industrial complex. The Beat Poetry of the 1950s also fed into the spirit of 1967. US intervention in South Vietnam was stepped up 1965, provoking increasing discontent within American society.

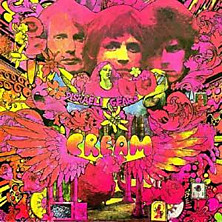

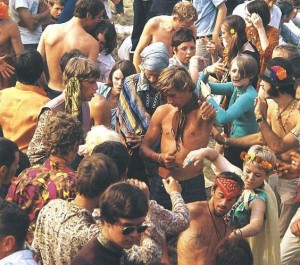

The Summer of Love effectively began on the 14 January 1967 with the ‘Human Be-In’ in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.[2] Former Harvard professor Timothy Leary attended and advocated those present to ‘turn on tune in and drop out’. To ‘drop out’ meant the ‘active, selective, graceful process of detachment from involuntary or unconscious commitments.’[3] By the spring of 1967 a Council for the Summer of Love had been established in San Francisco and the Haight –Ashbury district became the focal point for the counter-culture. Later in the year the Monterey pop festival was staged and the hit ‘San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flower in Your Hair)’ written by John Phillips (a member of The Mamas and the Papas) would become a lasting reminder of the year of the hippie. Across the Atlantic, London was still in a period in which it was designated a ‘swinging city’ and it hosted events such as the 14 Hour Technicolour Dream staged at the Alexandra Palace on 29 April. (to raise money for the underground publication International Times). The UFO (Underground Freak Out) club on Tottenham Court Road was the countercultural psychedelic hub. Whereas the Beatles had launched Mersey beat from the Liverpool venue the Cavern, at UFO The Pink Floyd similarly became the ‘house band’ and played psychedelic music (led by Syd Barrett) usually engulfed by psychedelic lighting. Indeed, 1967 saw the release of The Pink Floyd’s first LP The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (a title taken from Kenneth Graham’s Edwardian classic Wind in the Willows). It was the only one to feature Syd, who left the band due to mental issues probably linked to an excessive LSD intake. Other significant albums released in 1967 and possessed by most hippies were The Velvet Underground and Nico, by the Velvet Underground; Are You Experienced? by Jimmy Hendricks; Procul Harem by Procul Harem, Forever Changes by Love; Disraeli Gears by Cream (complete with a psychedelic cover); and Scott by Scott Walker.[4] In the field of literature 1967 was the year that Tolkien’s trilogy Lord of the Rings found a market amongst a hippie readership read as a countercultural text. Gandalf for President!

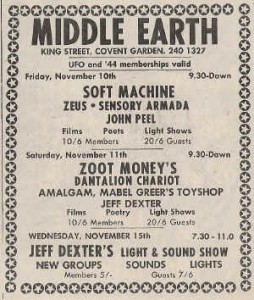

After UFO closed down due to police pressure, the epicentre of London hippiedom shifted to the Middle Earth Club in Covent Garden. For the Beatles, meanwhile, it was to be one of the most significant years of their career. In 1965 and 1966 the Beatles’ albums Rubber Soul and Revolver had witnessed a distinct change as the Fab Four began to shed their mop top image and they engaged with the drug culture. Their first encounter with LSD was in July 1965, when they were unwittingly given it by a ‘wicked dentist’ on the Edgware Road. It was placed on sugar cubes and put in John Lennon and George Harrison’s after-dinner coffee. [5] The Revolver LP subsequently contained the track ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ which was John Lennon’s musical take on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, a track which completely baffled producer George Martin when he first heard it. In 1967, the Beatles had their first encounter with the Maharishi Yogi, initially at the London Hilton and then when they attended a summer school in transcendental meditation in Bangor, North Wales. It was during this weekend in late August 1967 that they learned of the death of their manager Brian Epstein. Eastern religions were a significant part of the hippie culture and many, largely middle-class hippies, travelled to India, via Greece and Turkey to ‘find themselves.’ George Harrison learnt to play the sitar taking lessons from Ravi Shankar during this period and the sound of this instrument became associated with the Summer of Love (a sitar features on the track ‘Within You Without You’ on Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band). There were, moreover, a multitude of religious ‘sects’ or possibly more accurately, ‘cults’ that emerged in this period which in some instances accounted for missing persons, registered by worried family members.

At Westminster in 1967 the Wilson government oversaw the reforms of laws relating to homosexuality in England (not Scotland), abortion and family planning. These reforms partly facilitated the hippie ideal of ‘free love’. Communes were a feature of the period in locations such as Ladbroke Grove and Notting Hill Gate which in 1967 were rather run down districts, ‘bohemian chic’ and the hippie attitude to property would later feed into the squatting movement in British cities in the early 1970s.[6] Radio 1 first broadcast in 1967 and the Birmingham group The Move’s psychedelic single ‘Flowers in the Rain’ was the first track to be played on the station. Radio 1 was the BBC’s attempt to move into the territory hitherto held by the pirate radio stations, yet there were differences. The BBC retained Reithian values and would refuse to play any songs that appeared to advocate drug experimentation or indeed sexual references, such as the line ‘I’d love to turn you on’ on Lennon’s Pepper track ‘A Day in the Life,’ which had both sexual and drug connotations. Radio 1’s foremost patron of hippie rock was John Peel, who was in many respects, the ringmaster of the hippie scene.

Having withdrawn from touring at the end of August 1966, the group reassembled at Abbey Road to record what many critics argue to be their most significant work, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Incredibly, this album had no single releases on it (it was preceded earlier in the year by the double A-sided ‘Strawberry Fields/Penny Lane’ which famously only reached #2 in the charts behind ‘Please Release Me’ by Engelbert Humperdink) and this would become a feature of the later 1960s as the album signaled the arrival of mature rock (the album/LP) as opposed to juvenile pop (represented by the 45). Rock behemoth Led Zeppelin (1968-1980) took this to an extreme by never allowing singles to be released from any of their albums. The Beatles did release a non-Pepper single ‘All You Need is Love’ within a few weeks of the album’s appearance, a contribution to the ‘Our World’ broadcast which was the first global satellite link-up facilitated by the technological marvel that was the Post Office Tower (a physical manifestation of Wilson’s ‘White Heat’) which had begun to operate in 1965. The track would later feature on the second album of the year that the Fab Four released.

The Fool Collective Mural outside Apple Boutique, one of the Beatles’ fledgling Apple Corps enterprises.

At the death of the Summer of Love the Beatles’ manager was lost too. Brian Epstein’s overdose marked something of a crisis and his death partly provoked the creation of the Apple Corps, with its ambitious creative portfolio which included the opening of a Beatles’ boutique at 94 Baker Street. The Fool Collective (a group of Dutch artists) was commissioned to create a mural on the side of the building, which they duly undertook in November 1967. Yet Baker Street was not Haight-Ashbury. Westminster Council objected to the mural being placed on the building as they had not granted consent for this to be undertaken (it evidently contravened by-laws and building regulations) and local traders were not happy either. As a result the psychedelic mural was whitewashed the following year – thus mirroring and anticipating the White Album that the group released in 1968. In 1967 the Beatles would also make their third film (the first one directed and devised by the group themselves) – Magical Mystery Tour. The film was heavily influenced by English popular culture – the charabang booze-fuelled trip to the seaside and overladen with the trippy-hippy psychedelic ‘vibe’ that was in the air at this point in time. It was broadcast at the very end of the year, Boxing Day 1967, but unfortunately in black and white, thus negating the film’s real strength. American audiences were rather puzzled by this film as a coach trip to the seaside is a very English phenomenon. Other events in 1967 were the arrest of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards for drug possession at Richards’ West Wittering home Redlands, which provoked a debate in the media regarding the harsh treatment of the two Stones for what amounted to possession of pep pills.

The year after the Summer of Love was a more violent affair. This perhaps reflects the notion that peaceful protest was ineffective and more direct action was needed in order to enact change. The Stones reflected this change releasing ‘We Love You’ in 1967, but shifting their focus to the ‘Street Fighting Man’ in 1968.

1967 and its Legacy

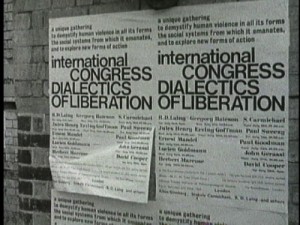

The legacy of the Summer of Love is disputed. Many of the hippies grew up and out of the counterculture. Many were corporatised and even threw their support in Britain behind a Lincolnshire grocer’s daughter at the election of 1979. Hippies who became entrepreneurs include the likes of Richard Branson and Steve Jobs. Peaceful protest, a feature of 1967 is certainly something that is still witnessed, the mid-1990s protest at the proposed Newbury by-pass (remember Swampy –where is he now? [7]) had perhaps direct lineage to ’67 as well as other protests in English history dating back centuries. So too, the Greenham Common Peace protests of the early 1980s which, of course, also fed back into the origins of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In terms of environmentalism, global warming was discussed at the Dialectics of Liberation conference held in London in July 1967 and the notion of ethical trading is also traceable to ’67.[8]

In the mid-1980s Bob Geldorf’s Live Aid project took the ‘Our World’ global link up of ’67 to a much grander scale, given more powerful international satellite technology by this period. At the end of the 1980s a second summer of love was recognised, with ecstasy added to LSD as the drug of choice of the 24-hour party people.[9]

Madchester Graffiti – The Second Summer of Love 1989. This time the regions (Manchester) led the way in the new psychedelia.

Opinions are divided as to how far Britain and the USA were different places after 1967. Writing on the thirtieth anniversary of the Summer of Love, Barry Hugill believed 1967 marked a decisive break with the old Britain: ‘The stuffy conformism of the long post war period gave way to a new emphasis on personal freedom.’[10] He cites homosexual law reform, a new race relations act and the birth of the women’s liberation movement as evidence. The latter was, however, a by-product of the male chauvinism inherent in the hippie movement which had branded women as ‘chicks’. Timothy Miller, reflecting on the hippie legacy in the USA, noted that by 1989 ‘over seventy million Americans, close to 30 per cent of the population, had used one or more illicit drugs at some time in their lives.’[11] Attitudes to sex became more liberal from the later 1960s, more informal ways of dressing date from ’67 and the New Age movement owed much to hippiedom. The idea of students backpacking across the globe during a university gap year is traceable back to this period too.[12] Others sound a more cautious note. Barry Miles concluded his recollections of the 1960s by observing ‘Though Britain is more of a meritocracy now, it is still not a land of equal opportunity … There is no written constitution or Bill of Rights …and Britain still censors more of what its people can read or view than any other European nation.’[13] The free love ethic of ’67 was much reduced by the AIDS scare of the 1980s, and right of centre of governments in both the USA and UK blamed many of society’s ills on the 1960s, and (especially 1967) whether justified or not. One of the most interesting pieces of journalistic reflection on 1967 was a feature written by Daniel Finkelstein on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the Summer when he asked:

Why do we call it the Summer of Love? In the hot months of 1967 there was a military coup in Greece, a war started in Biafra, there were race riots in Newark, Detriot and Boston, Muhammed Ali was stripped of his world title for refusing the draft; Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were jailed on drugs charges, Arab attempts to destroy Israel triggered the Six Day War, Kennetth Halliwell murdered his lover, the playwright Joe Orton, the Beatles’ manager died of a drug overdose and the Swedish switched to driving on the right.[14]

He moved on to argue that only a tiny percentage of America’s youth participated in the counterculture, and George Harrison wasn’t impressed when he arrived in the Haight-Ashbury district in August 1967. The Summer of Love and the counterculture Finkelstein argued, have been colonised by the left when, in fact, the political right had (and have) as much claim to the 1960s more generally because the decade saw the rise in affluence amongst the middle and working classes, by which he argues, youth culture was enabled. The anti-consumerist hippie ideology did indeed struggle to hold back rampant consumerism in the 1970s and 1980s. Ironically as a reflection of this, The Pink Floyd had by the mid-1970s dropped the definitive article from the group’s name and were selling millions of LPs as they transformed their sound into Adult Orientated Rock (AOR). So too, new musical genres such as glam rock (1971-1975), punk rock (1976-1978) and post-punk (1978-1984), tended to override the hippie rock of 1967-1970.

There is more that can be added to the idea that the Summer of Love’s events had only a limited number of participants. Thinking of my own parents’ ‘life trajectory’ in this decade, I’m always struck by how little of the counterculture impinged on their lives. When I looked through their record collection I saw not a single Beatles record, nor one by the Stones for that matter. My father was 26 when the 1960s began, thus he was too old to participate in the youth culture of the later 1960s, he appears to have preferred classical music and was a little too old for rock and roll. I did find a copy of ‘Rock Island Line’ by Lonnie Donnegan in the collection, which suggests the skiffle craze of the later 1950s did hold some allure. However, instead of sit-ins (neither of my parents attended university) or drug taking, love-ins or meditation, my parents were primarily home builders (unlike their parents they bought their own home) and had a child (me). My parents were not exceptional. Theirs is a far more common story of the sixties and we do need to appreciate that the Summer of Love was limited to a particular age group (18-25-year olds predominantly), hence the hippie slogan was ‘never to trust anyone over 30’ and particular locations (London).

Psychedelia did not seem to go down well outside the capital. The provincial city had a more working-class profile compared to London and a far more limited bohemian scene. There is also theory that taking an LSD trip was inadvisable if using heavy machinery and it was better to take amphetamines on a Saturday night, as the effects would have worn off by the start of the working week. Several of the pop and rock ‘fraternity’ testify to this lack of provincial interest in psychedelia. Andy Summers recollects that as far as psychedelia was concerned ‘In the Roundhouse, the UFO and the Middle Earth Club in London everyone seems to get it [but outside London] ‘we are greeted with stunned silence.’[15] Nick Mason, noted that if Pink Floyd played their psychedelic freak out track ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ outside London, ‘people hated it.’[16] Bill Ward, drummer in the heavy metal group Black Sabbath grew up, as did the other members in Aston, Birmingham. He notes in explaining the sound of the group ‘Peace and love was not necessarily a reality. We came from Aston…there wasn’t a whole lot of flowers being handed out in Aston, few boots and a kick in the head …a few razor cuts…it was a tough town.’[17] Sheffield club owner Peter Stringfellow recollected that when he renamed his King Mojo club the Beautiful King Mojo club in 1967 it was a flop with the punters. When Stringfellow threw petals into a Nottingham club crowd, they threw coke cans back at him in return. His sitar music didn’t go down well either.[18]

In Birmingham the first ‘love-in’ was organised by John Singer at the Carlton Ballroom, Erdington in ’67. It was a flop. ‘What it all boils down to’ said Singer, ‘this evening isn’t very different from any other Saturday night at the Carlton.’[19] Maureen Callaghan a 20-year-old antique shop assistant came to the love-in and said ‘It don’t know anything about flower power or hippies…I’m just like most people in Birmingham people here….We’ve all heard about flower power and came along for a dekko… but we all know this craze won’t last.’[20] She was right. According to the Deep Purple keyboard player Jon Lord, kaftans were removed as the British winter arrived (October 1967) and the craze waned thereafter.[21] Press reports noted that whilst in 1969 there were no arrests for LSD possession in Birmingham in 1970, there were 15. [22] There were delays in the realm of rock music too. In 1968, in a shift from the pre-Beatles era to the post, Carlton Ballroom changed its name to ‘Mothers’ and became one of the most significant provincial venues at which prominent rock bands of the era appeared. Pink Floyd for example, recorded part of their 1969 Ummagumma LP at the venue. So, whilst the Summer of Love was late in arriving in the provinces, it did nevertheless arrive, around three years late.

John Griffiths is a senior lecturer in History at Massey University. His current project is titled Beyond Swinging London and examines provincial city culture in the period 1964-1974. The project considers the ways in which the culture emanating from the Capital and the counter cultural period c.1967-1973 more generally affected the regional city. It examines fashion, counter cultural publications and venues, youth cultures and attitudes towards the permissive society in the regions.

Want to Read more about the Summer of Love?

M. Collins, ‘The Beatles’ Politics’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations 16 (2014), 291-309.

C. Grunenberg and J. Harris (eds.), Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and the Counterculture in the 1960s (Liverpool, 2005).

B. Miles, In the Sixties (London, 2002).

B. Miles, Hippies (New York, 2004), chapter on 1967.

T. Miller, The Hippies and American Values (Knoxville, 1991).

R. Neville, Play Power, (London, 1970)

R. Neville, Hippy Hippy Shake (London, 1995).

P. Oliver, Hinduism and the 1960s: The Rise of a Counter Culture (London, 2014).

References

[1] An exhibition titled ‘Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia’ is currently being at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive at the University of California Berkeley, 8 Feb – 21 May 2017.The proposal to stage a Summer of Love music festival, in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco was denied by the city’s Recreation and Parks Department.

[2] B. Miles, Hippie (New York, 2003), 186-191. A less ambitious gathering was staged in the UK at Woburn Abbey in August 196, The Times 4 May 2009, 53.

[3] T. Leary, Flashbacks: A Personal and Cultural History of an Era (Los Angeles, 1983), 253.

[4] P. Morley, The Age of David Bowie: How David Bowie Made a World of Difference (London, 2016), 159.

[5] ‘The Dental Experience’ in The Beatles Anthology (San Francisco, 2000), 177.

[6] J. White, London in Twentieth Century: A City and its People (London, 2001), 349-350.

[7] As of 2013 living in a commune in Wales.

[8] http://www.dialecticsofliberation.com/1967-dialectics/the-dialectics-of-liberation-redialled/ Also B.Miles In the Sixties (London, 2003), 223.

[9] The Times, 6 June 2009, p. 34.

[10] B. Hugill, ‘We Are All Children of ‘67.’ The Observer 25 May 1997.

[11] T. Miller, The Hippies and American Values, (Knoxville, 1991), 130.

[12] Ibid., 131, 136. The Hippies were in a sense anti-fashion, in that they reject consumerism as an aspect of capitalism. Their fashion often took the form of tie-dyed clothing which was a ‘do-it yourself fashion’ and looked psychedelic. Thanks to Grainne Goodwin for flagging ‘backpacking’ to me.

[13] Miles, In the Sixties, 304.

[14] ‘The Hippies Were Wrong: Money Can Buy You Love.’ The Times, 13 June 2007, 19.

[15] A. Summers, One Train Later (London, 2006), 123.

[16] Comment made in Pink Floyd & The Syd Barrett Story BBC DVD 2001. Mike Watkinson and Peter Anderson also note that when Pink Floyd played outside London they were sometimes bottled off stage. Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett & the Dawn of Pink Floyd (London, 2001), 45.

[17] See Ward’s comments in the BBC 4 documentary Heavy Metal Britannia first broadcast in 2010.

[18] P. Stringfellow, ‘My Summer of Love.’ The Independent 5 May 2007.

[19] Birmingham Evening Mail, 28 August 1967, 4.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Comments made in DVD listed in footnote 17.

[22] Birmingham Post, 30 March 1971, 14.