Since its foundation in 1976 Social History has published over 200 articles on the history of the European continent from antiquity to the contemporary period. This Virtual Special Issue aims to showcase our best writing on European social history, highlight the range and diversity of material in the journal, and show how Social History has encouraged critical reflection on the methodologies, historiographies and approaches that shape these fields. As an international academic journal, Social History explores how lives are lived, understood and made sense of over time, without restriction of place. The topics covered over the last four decades have been eclectic and broad. Whilst reflecting the opening up of new areas of enquiry, many remain perennially relevant. This Virtual Special Issue includes work from the early days of the journal on violence, capitalism and the modern state (by Alf Lüdtke) and on the politics of language and national identity (by Patrice L. R. Higonnet) which are pertinent to debates today in Europe and beyond. Early modern responses to child poverty and street begging are the focus of Joel Harrington’s article, which also deals with the history of children and young people and the production of popular culture. Over the years Social History has published a number of important interventions on witchcraft, magic and popular belief, reflected here in the article by Marijke Gijswijt‐Hofstra, which offers insights from the Dutch perspective. Court records – providing a crucial lens on social conflict and its resolution as well as the construction of social identify, honour and reputation – are explored here by Trevor Dean in his study of gender and insult in late-medieval Bologna. In recent years contributors to the journal have offered important re-assessments of the experiences of the twentieth century – armed conflict, fascism, socialism, the Cold War and its aftermath – across Europe and the Soviet bloc. Two pieces have been selected here as exemplary of these new approaches. Anna Krylova’s article argues for a more nuanced understanding of Soviet subjectivity – ‘of imagining and living socialism’ – which does not simply reduce it to an unswerving Bolshevik origin. The social history of the environment – and in particular of garbage and waste management – provides the impetus for Anne Berg’s examination of the politics of recycling in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe, which she compelling shows ‘were intimately connected’ to the Third Reich’s ‘destructive fantasies of purification’ (453). Social […]

Continue reading →

On 1 March 1981 a hunger strike organised by paramilitary republican prisoners got underway at the Maze (Long Kesh) H-blocks prison in Northern Ireland as part of the prisoners’ ongoing campaign to obtain political prisoner status and its accompanying privileges. The strike was initiated by Gerard (‘Bobby’) Sands and ten strikers died before the strike was called off on 3 October. The recently established Islamic Republic of Iran (founded on 1 April 1979) engaged in extensive propaganda campaign in support of the Irish republican hunger strikers under the banner of solidarity with anti-imperialist struggles and the downtrodden peoples around the world. This was an additional opportunity for the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) to condemn what it cast as British imperialism and its brutality, by appropriating and reframing the Irish republican struggle. Continue reading

On 1 March 1981 a hunger strike organised by paramilitary republican prisoners got underway at the Maze (Long Kesh) H-blocks prison in Northern Ireland as part of the prisoners’ ongoing campaign to obtain political prisoner status and its accompanying privileges. The strike was initiated by Gerard (‘Bobby’) Sands and ten strikers died before the strike was called off on 3 October. The recently established Islamic Republic of Iran (founded on 1 April 1979) engaged in extensive propaganda campaign in support of the Irish republican hunger strikers under the banner of solidarity with anti-imperialist struggles and the downtrodden peoples around the world. This was an additional opportunity for the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) to condemn what it cast as British imperialism and its brutality, by appropriating and reframing the Irish republican struggle. Continue reading

On 1 March 1981 a hunger strike organised by paramilitary republican prisoners got underway at the Maze (Long Kesh) H-blocks prison in Northern Ireland as part of the prisoners’ ongoing campaign to obtain political prisoner status and its accompanying privileges. The strike was initiated by Gerard (‘Bobby’) Sands and ten strikers died before the strike was called off on 3 October. The recently established Islamic Republic of Iran (founded on 1 April 1979) engaged in extensive propaganda campaign in support of the Irish republican hunger strikers under the banner of solidarity with anti-imperialist struggles and the downtrodden peoples around the world. This was an additional opportunity for the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) to condemn what it cast as British imperialism and its brutality, by appropriating and reframing the Irish republican struggle. Continue reading

On 1 March 1981 a hunger strike organised by paramilitary republican prisoners got underway at the Maze (Long Kesh) H-blocks prison in Northern Ireland as part of the prisoners’ ongoing campaign to obtain political prisoner status and its accompanying privileges. The strike was initiated by Gerard (‘Bobby’) Sands and ten strikers died before the strike was called off on 3 October. The recently established Islamic Republic of Iran (founded on 1 April 1979) engaged in extensive propaganda campaign in support of the Irish republican hunger strikers under the banner of solidarity with anti-imperialist struggles and the downtrodden peoples around the world. This was an additional opportunity for the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) to condemn what it cast as British imperialism and its brutality, by appropriating and reframing the Irish republican struggle. Continue reading

Historians have long been aware of the existence of 19th -century data on prisoner literacy, even if they have been shy about making use of it. The expansion of prison education in the early 19th century meant that the practice of assessing prisoners’ literacy skills became widespread, and from 1835 keepers of prisons were asked to return numbers of prisoners who could read, read and write, and do neither to the Home Office for inclusion in national criminal and penal statistics. However, much less is known about a related activity, the collection of evidence on prisoners’ schooling at a number of penal institutions across England.

Historians have long been aware of the existence of 19th -century data on prisoner literacy, even if they have been shy about making use of it. The expansion of prison education in the early 19th century meant that the practice of assessing prisoners’ literacy skills became widespread, and from 1835 keepers of prisons were asked to return numbers of prisoners who could read, read and write, and do neither to the Home Office for inclusion in national criminal and penal statistics. However, much less is known about a related activity, the collection of evidence on prisoners’ schooling at a number of penal institutions across England.  We often think of comfort in terms of physical ease or well-being – epitomised in the comfy armchair; but it also has emotional aspects, both in terms of feeling comfortable (or uncomfortable) in a particular situation and seeking comfort in bereavement or at other times of stress. This complexity was perhaps even more evident in the early nineteenth century, a growing desire for physical comfort was apparent in sofas and easy chairs, hearths that threw heat out into the room, and lamps that improved the lighting of rooms that were increasingly laid out in a manner that was convenient for modern, informal ways of living. Yet all of these were layered onto a persistent and very human need for emotional support.

We often think of comfort in terms of physical ease or well-being – epitomised in the comfy armchair; but it also has emotional aspects, both in terms of feeling comfortable (or uncomfortable) in a particular situation and seeking comfort in bereavement or at other times of stress. This complexity was perhaps even more evident in the early nineteenth century, a growing desire for physical comfort was apparent in sofas and easy chairs, hearths that threw heat out into the room, and lamps that improved the lighting of rooms that were increasingly laid out in a manner that was convenient for modern, informal ways of living. Yet all of these were layered onto a persistent and very human need for emotional support.  Since its foundation in 1976 Social History has published over 200 articles on the history of the European continent from antiquity to the contemporary period. This Virtual Special Issue aims to showcase our best writing on European social history, highlight the range and diversity of material in the journal, and show how Social History has encouraged critical reflection on the methodologies, historiographies and approaches that shape these fields. As an international academic journal, Social History explores how lives are lived, understood and made sense of over time, without restriction of place. The topics covered over the last four decades have been eclectic and broad. Whilst reflecting the opening up of new areas of enquiry, many remain perennially relevant. This Virtual Special Issue includes work from the early days of the journal on violence, capitalism and the modern state (by Alf Lüdtke) and on the politics of language and national identity (by Patrice L. R. Higonnet) which are pertinent to debates today in Europe and beyond. Early modern responses to child poverty and street begging are the focus of Joel Harrington’s article, which also deals with the history of children and young people and the production of popular culture. Over the years Social History has published a number of important interventions on witchcraft, magic and popular belief, reflected here in the article by Marijke Gijswijt‐Hofstra, which offers insights from the Dutch perspective. Court records – providing a crucial lens on social conflict and its resolution as well as the construction of social identify, honour and reputation – are explored here by Trevor Dean in his study of gender and insult in late-medieval Bologna. In recent years contributors to the journal have offered important re-assessments of the experiences of the twentieth century – armed conflict, fascism, socialism, the Cold War and its aftermath – across Europe and the Soviet bloc. Two pieces have been selected here as exemplary of these new approaches. Anna Krylova’s article argues for a more nuanced understanding of Soviet subjectivity – ‘of imagining and living socialism’ – which does not simply reduce it to an unswerving Bolshevik origin. The social history of the environment – and in particular of garbage and waste management – provides the impetus for Anne Berg’s examination of the politics of recycling in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe, which she compelling shows ‘were intimately connected’ to the Third Reich’s ‘destructive fantasies of purification’ (453). Social […]

Since its foundation in 1976 Social History has published over 200 articles on the history of the European continent from antiquity to the contemporary period. This Virtual Special Issue aims to showcase our best writing on European social history, highlight the range and diversity of material in the journal, and show how Social History has encouraged critical reflection on the methodologies, historiographies and approaches that shape these fields. As an international academic journal, Social History explores how lives are lived, understood and made sense of over time, without restriction of place. The topics covered over the last four decades have been eclectic and broad. Whilst reflecting the opening up of new areas of enquiry, many remain perennially relevant. This Virtual Special Issue includes work from the early days of the journal on violence, capitalism and the modern state (by Alf Lüdtke) and on the politics of language and national identity (by Patrice L. R. Higonnet) which are pertinent to debates today in Europe and beyond. Early modern responses to child poverty and street begging are the focus of Joel Harrington’s article, which also deals with the history of children and young people and the production of popular culture. Over the years Social History has published a number of important interventions on witchcraft, magic and popular belief, reflected here in the article by Marijke Gijswijt‐Hofstra, which offers insights from the Dutch perspective. Court records – providing a crucial lens on social conflict and its resolution as well as the construction of social identify, honour and reputation – are explored here by Trevor Dean in his study of gender and insult in late-medieval Bologna. In recent years contributors to the journal have offered important re-assessments of the experiences of the twentieth century – armed conflict, fascism, socialism, the Cold War and its aftermath – across Europe and the Soviet bloc. Two pieces have been selected here as exemplary of these new approaches. Anna Krylova’s article argues for a more nuanced understanding of Soviet subjectivity – ‘of imagining and living socialism’ – which does not simply reduce it to an unswerving Bolshevik origin. The social history of the environment – and in particular of garbage and waste management – provides the impetus for Anne Berg’s examination of the politics of recycling in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe, which she compelling shows ‘were intimately connected’ to the Third Reich’s ‘destructive fantasies of purification’ (453). Social […]  On 4 July 1927, the French Minister of the Interior, Albert Sarraut, wrote confidentially to the prefect of the Normandy département of Seine-Inférieure requesting immediate action to prevent the section of the ‘Indochinese Mutual Association’ based in Le Havre from distributing the newspaper Viet Nam Hon. Sarraut warned the prefect that ‘revolutionary propaganda generated in Paris could have regrettable repercussions in Indochina’ and that it was suspected that the most important departure point for copies of the newspaper was Le Havre. The letter identified one Dang Van Thu, a colonial migrant and protégé from the French protectorate of Annam, owner of the Restaurant Intercolonial in the rue Saint Nicolas, as leader of the ‘Indochinese Mutual Association’ and an instrumental figure in the distribution of the newspaper that was provoking anxiety in Paris.[1]

On 4 July 1927, the French Minister of the Interior, Albert Sarraut, wrote confidentially to the prefect of the Normandy département of Seine-Inférieure requesting immediate action to prevent the section of the ‘Indochinese Mutual Association’ based in Le Havre from distributing the newspaper Viet Nam Hon. Sarraut warned the prefect that ‘revolutionary propaganda generated in Paris could have regrettable repercussions in Indochina’ and that it was suspected that the most important departure point for copies of the newspaper was Le Havre. The letter identified one Dang Van Thu, a colonial migrant and protégé from the French protectorate of Annam, owner of the Restaurant Intercolonial in the rue Saint Nicolas, as leader of the ‘Indochinese Mutual Association’ and an instrumental figure in the distribution of the newspaper that was provoking anxiety in Paris.[1]  The study of material culture has grown hugely in recent years. For the historian, focusing on objects instead of (or, rather, alongside) more familiar source types such as texts, images or numerical data involves a very different way of working, both practically and intellectually. As someone who is relatively new to this field, I am acutely aware of this at the moment. My article in the current issue of Social History entitled ‘Boots, material culture and Georgian masculinities’ is the culmination of a project that I have been working on for a few years now. Although I had written about material culture before, in my book Embodying the Militia in Georgian England, this was the first time that objects had been at the forefront of my approach and had really driven my conclusions.[1]

The study of material culture has grown hugely in recent years. For the historian, focusing on objects instead of (or, rather, alongside) more familiar source types such as texts, images or numerical data involves a very different way of working, both practically and intellectually. As someone who is relatively new to this field, I am acutely aware of this at the moment. My article in the current issue of Social History entitled ‘Boots, material culture and Georgian masculinities’ is the culmination of a project that I have been working on for a few years now. Although I had written about material culture before, in my book Embodying the Militia in Georgian England, this was the first time that objects had been at the forefront of my approach and had really driven my conclusions.[1]  To commemorate the bicentenary of the Pentrich rising, the University of Derby organised a one-day conference which brought together academics and interested members of the public. This included representatives from the Pentrich and South Wingfield Revolution group who have co-ordinated a series of events marking two hundred years since the rising. A number of the papers touched on Pentrich to varying degrees, but the brief of speakers was to situate the rising in the context of the febrile underworld of radicalism and protest in the run-up to the tragic events of the night of 9-10 June 1817.

To commemorate the bicentenary of the Pentrich rising, the University of Derby organised a one-day conference which brought together academics and interested members of the public. This included representatives from the Pentrich and South Wingfield Revolution group who have co-ordinated a series of events marking two hundred years since the rising. A number of the papers touched on Pentrich to varying degrees, but the brief of speakers was to situate the rising in the context of the febrile underworld of radicalism and protest in the run-up to the tragic events of the night of 9-10 June 1817.  A national museum dedicated to the British Army has existed in some form since 1960. The current site of the museum, in London’s resplendent Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, has been standing since the early 1970s. After closing in May 2014 for a revamp, on 30 March 2017 the National Army Museum opened its doors again to the visiting public. A visitor, like myself, who may not have visited the museum before its renovation might feel both hampered and liberated by a lack of comparison with its pre-2014 incarnation: hampered by possessing less points of comparison in light of its £23.75m renovation, and benefited in that visitors can view the newly opened site unprejudiced by past experiences. Indeed, this seems to be the intention of the museum’s designers and directors, with a potted history of the museum’s development conspicuously missing from its website. But from what can be gleaned from a cursory online search, it is apparent that the revamp is a great improvement. This review will focus on the permanent exhibitions in particular, taking into account their particular renderings of historical narrative in relation to a national history of the British Army.

A national museum dedicated to the British Army has existed in some form since 1960. The current site of the museum, in London’s resplendent Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, has been standing since the early 1970s. After closing in May 2014 for a revamp, on 30 March 2017 the National Army Museum opened its doors again to the visiting public. A visitor, like myself, who may not have visited the museum before its renovation might feel both hampered and liberated by a lack of comparison with its pre-2014 incarnation: hampered by possessing less points of comparison in light of its £23.75m renovation, and benefited in that visitors can view the newly opened site unprejudiced by past experiences. Indeed, this seems to be the intention of the museum’s designers and directors, with a potted history of the museum’s development conspicuously missing from its website. But from what can be gleaned from a cursory online search, it is apparent that the revamp is a great improvement. This review will focus on the permanent exhibitions in particular, taking into account their particular renderings of historical narrative in relation to a national history of the British Army.  After the October revolution of 1917, venereal diseases formed part of a long list of social phenomena that Soviet leaders deemed completely incompatible with socialist society. Not only were these diseases remnants of the decadence and corruption of the bourgeois capitalist past, their debilitating effects endangered the construction of the new state and way of life (byt’). Venereal diseases were diagnosed and treated as part of the field of ‘social hygiene’, driven by the idea that they were both biological and social phenomena, best understood within their social context.[1] In light of this, Soviet officials emphasised the need for an urgent ‘struggle’ (bor’ba) against what they perceived to be the main causes of infection: prostitution, promiscuity, and poor hygiene. Official responses to the problem of venereal diseases swung between repression and welfare, advocating patient confidentiality on the one hand, and justifying interventions into the private sphere on the other.

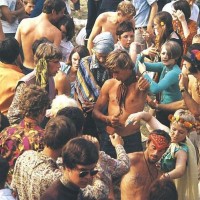

After the October revolution of 1917, venereal diseases formed part of a long list of social phenomena that Soviet leaders deemed completely incompatible with socialist society. Not only were these diseases remnants of the decadence and corruption of the bourgeois capitalist past, their debilitating effects endangered the construction of the new state and way of life (byt’). Venereal diseases were diagnosed and treated as part of the field of ‘social hygiene’, driven by the idea that they were both biological and social phenomena, best understood within their social context.[1] In light of this, Soviet officials emphasised the need for an urgent ‘struggle’ (bor’ba) against what they perceived to be the main causes of infection: prostitution, promiscuity, and poor hygiene. Official responses to the problem of venereal diseases swung between repression and welfare, advocating patient confidentiality on the one hand, and justifying interventions into the private sphere on the other.  Additions to the Western lexicon Hipster (1941): someone who is ‘Hip’ or in touch with the fashion. Hippy (1953): originally Hipster (1941) was used but then ‘Hippy’ became the term to use in the 1960s to denote West Coast American youth rejecting conventional society. Flower Children/Flower People (1967): alternative name for Hippies. see above. Freak (1967): Someone who freaks out on drugs Generation Gap (1967): Difference in outlook between older and younger people. Groupie (1967): a young female fan of rock group. ‘Love In’/‘Be-In’ (1967) : communal acts usually by students. ‘Straight’ (1967): Someone who conforms to conventions of society. Vibes (1967): instinctive feelings. Source: John Ayto 20th Century Words (Oxford, 1999). This year, 2017, will witness the fiftieth anniversary of what subsequently became known as the ‘Summer of Love.’[1] One of its legacies as can be seen above, was to add to the Western lexicon. Indeed, 1967 was the year in which the counterculture became ‘visible’ in Western society and the underground came up for air. This was to be the year of the ‘hippies,’ or the ‘flower children’ as they were also known.

Additions to the Western lexicon Hipster (1941): someone who is ‘Hip’ or in touch with the fashion. Hippy (1953): originally Hipster (1941) was used but then ‘Hippy’ became the term to use in the 1960s to denote West Coast American youth rejecting conventional society. Flower Children/Flower People (1967): alternative name for Hippies. see above. Freak (1967): Someone who freaks out on drugs Generation Gap (1967): Difference in outlook between older and younger people. Groupie (1967): a young female fan of rock group. ‘Love In’/‘Be-In’ (1967) : communal acts usually by students. ‘Straight’ (1967): Someone who conforms to conventions of society. Vibes (1967): instinctive feelings. Source: John Ayto 20th Century Words (Oxford, 1999). This year, 2017, will witness the fiftieth anniversary of what subsequently became known as the ‘Summer of Love.’[1] One of its legacies as can be seen above, was to add to the Western lexicon. Indeed, 1967 was the year in which the counterculture became ‘visible’ in Western society and the underground came up for air. This was to be the year of the ‘hippies,’ or the ‘flower children’ as they were also known.